A quarter of a century later, Homeworld still captures the imagination – but is this the return to form we’re looking for?

Homeworld 3 developers Blackbird Interactive proved both their design chops and their love of the Homeworld franchise by creating Deserts of Kharak in 2016, a game that started out as a cheeky unauthorised take on the Homeworld space strategy formula on dry land and ended up a critically-acclaimed official part of the series with the blessing of new brand IP owner Gearbox. Eight years later, with the even more successful Hardspace: Shipbreaker in the books and a successful crowd-funding campaign, the third mainline Homeworld 3 game is finally here.

Given that long history and a protracted development with several delays, it’s perhaps no surprise that HW3 is a flawed but deeply fascinating game – one that successfully recreates the satisfying 3D ship battlescapes and impeccable space vibes of its genre-defining predecessors, only to be somewhat let down by an inexpertly told story and some mechanical stumblings.

Let’s start with the good stuff: the collection of missions that make up the 10-hour campaign are varied and fun, starting with simple skirmishes amongst basic strikecraft and concluding with massive fleet battles against well-equipped enemies. Along the way, you’ll escape natural phenomena, skulk around searching patrols and navigate within and along massive megalithic structures. Your fleet persists from one mission to the next, so there are clear incentives for keeping your best units alive and capturing the ships of your foes whenever possible. Each unit has an upgradeable ability to make it better in certain scenarios, and tends to excel against one unit type while failing against others, encouraging mixed fleets.

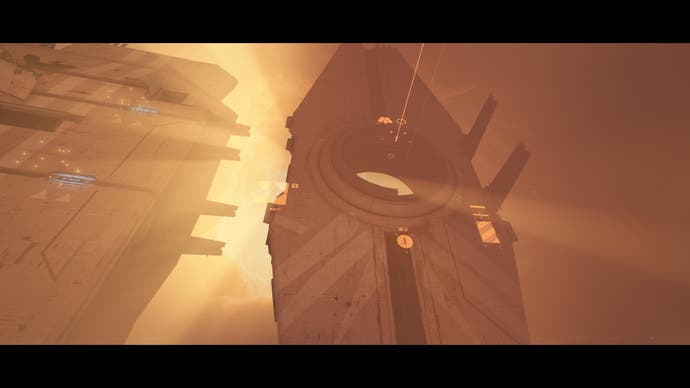

The original Homeworld titles released between 1999 and 2003 offered elegant 3D combat in deep space, with ephemeral nebulae and damaging asteroid fields filling the gaps between swooping enemy fleets, but in Homeworld 3 the action tends to be centred amongst large hyperspace gates and other massive structures, giving you and your enemies cover to conceal and protect your forces. It’s an interesting idea, amusingly backed up in-universe by your Intel officer’s insistence on practicing “modern” close quarter tactics, and does make engagements feel different. You can hide bombers behind a bit of floating debris to give them a clear shot at an enemy capital ship, or rush your fighters through huge tunnels to bypass enemy fortifications, but more often you’re just fighting in cramped quarters, with a massed blob of spacecraft senselessly emitting lasers, rail guns and torpedos in all directions as your frame-rate plummets well below a smooth 60fps.

Thankfully, even in these clumsier moments, the game looks and sounds fantastic. Homeworld’s original recipe of colourful, trail-emitting spaceships amongst pretty but static nebula skyboxes was as much the product of performance limitations as it was deliberate design, but it still works in 2024. Modern tech allows for some advantages, of course: more detailed spaceships, ray-traced shadows and strikingly lit stages.

The soundtrack is also top-notch, with long-time series composer Paul Ruskay providing tunes that run the gamut from haunting ambient fare to more densely layered electronica featuring Middle Eastern and Indian instruments. A new version of Adagio for Strings / Agnus Dei, the iconic Samuel Barber choral / classical piece that accompanies one of the best-known moments in the original Homeworld, also returns in moments that reference the events of the older games, which is a lovely touch. The ‘battle chatter’ between the various pilots in the fleet is also well-realised once again, with these natural-sounding conversations between flight crews providing extra ambiance – you can expect almost bored reports when things are quiet, and more frantic alerts as ships enter battle or trigger their special abilities.

Things get hectic pretty often too, as on top of the nontrivial task of directing ships in 3D space in real time, you’re often beset by large numbers of enemies that attack from different angles and require different responses. Annoying smart missle frigates pelt your larger ships from range, capture corvettes steal your frigates away while you’re distracted and anti-strikecraft turrets prove murderous to smaller vessels if left alive.

Thankfully, you have some tools to keep things under control. You’re able to slow down time in 25 percent increments or even pause entirely while you’re placing orders. There’s also the sensors manager, a kind of abstracted and distant view of the battlefield and its forces, though the crowded nature of combat and unclear iconography meant this blue screen was often harder to read than the standard view. Camera controls are excellent, with both modern real-time strategy and legacy Homeworld presets you can choose between freely. Finally, you also get the usual RTS staples of control groups and hotkeys that select all units of a given class – very useful given that you’ll often be augmenting groups with newly-produced replacements to ensure you stay within the game’s strict unit count limits.

The only thing missing with regard to the controls are pilots that actually follow your gosh-darn orders – something that Blackbird has at least slightly improved in patch 1.1 and highlighted as a priority for future updates too. Frequently you’ll ask a ship to back away from certain death, and they’ll either ignore the call or respond so lazily that they’ll lose almost all of their hitpoints in the process. You also can’t dock smaller ships to a specific carrier or mothership – they’ll just go to the closest one, often splitting groups unnecessarily – and the stop command seems purely decorative. You can set formations for your ships, but new additions to the squadron do their own thing and often leaving ships out of formation seems to be best for combat efficiency. It’s a far cry from the older Homeworld games, which feel snappy and responsive in comparison. Perhaps it’s a natural result of the more complicated terrain, but it saps a lot of the fun of the experience.

There’s a similar feeling of regression with regard to Homeworld 3’s storytelling. A great story isn’t always essential for a successful RTS, but the original Homeworld from 1999 has one of the best conceits of any video game: the warring tribes of your world, Kharak, discover a gargantuan spaceship buried deep in the desert, complete with a hyperspace core that allows FTL travel and a simple diagram with the ancient word for ‘home’ enscribed next to a distant arm of the galaxy. The factions unite, a giant mothership is built over the next 100 years to escape looming ecological disaster, and all is going swimmingly until the mothership pops out for its first hyperspace test and returns to find Kharak reduced to cinders by an enemy fleet settling an ancient grudge. It’s a simple yet compelling story of a people, whose motivations and goals are always clear.

By contrast, Homeworld 3 is a more personal story. Yes, you’re piloting another mothership, again sent to save your people and uncover a mystery, but this time you’re put in the shoes of a single person: Imogen S’Jet. As the granddaughter of Homeworld 1/2 mothership ‘pilot’ Karan, you’re sent to continue her investigation into why the hyperspace network that connects the galaxy is mysteriously going dark. The people of the titular homeworld send you off on your mission and swear you off to radio silence, so you’re left with a tight cast of characters: Imogen, close companion and Intel officer Isaac, the lost Karan and the antagonist ‘Ircarnate Queen’.

Character-driven sci-fi is a rich vein to explore – as proven by developer Blackbird Interactive’s previous work, Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak, to say nothing of other media like Battlestar Galactica – but what’s here never quite lands. We don’t learn much about the characters, and they don’t show much (if any) growth over the course of the game. The chief avenue of exposition is the characters shouting at each other a bit in a kind of interstellar Zoom call between missions, with basic facial animation and stiff, limited movement. It’s clear the ambition is here, but it’s much harder to sell this style versus the narrated art slideshows of Homeworld 1 or even the unit portrait character briefings of StarCraft.

The focus on a single villain requires some measure of charisma, motivation and capability to be effective, yet the Ircarnate Queen here lacks all three. She’s simultaneously powerful enough to be slowly consuming the galaxy and holding an entire army in her psychic thrall, yet foolish enough to lose every fight against you and believe every lie you tell her, so your eventual victory doesn’t feel particularly well-earned. There’s little mystery about her powers here either, compared to facing off against the impossibly vast Taiidan empire in Homeworld 1 or the unknowable, bio-mechanical virus of the Beast in Homeworld: Catacylsm.

While the campaign isn’t best helped by its story, the other modes on offer aren’t any more convincing. The roguelite ‘War Games’ mode seems promising, offering a choice of starting fleets and random upgrade artifacts that unlock possibilities not found in the campaign, but the moment-to-moment gameplay is simply moving around a map, fighting enemies, clicking on upgrades every once in a while and then warping to the next zone when you get overwhelmed by an impossibly large mob of enemies. The meta-progression that makes roguelites fun is light on the ground, and there’s little of the variety that makes the campaign missions exciting.

Multiplayer also has its challenges, with the large and wide-open maps rife for sneaky hyperspace jumps from the earlier games replaced by brutally fast close-quarter combat with no jumps allowed – it’s like having a boxing match in a phone booth. Add on the many glitches and omissions detailed by the (largely disappointed) denizens of the Homeworld 3 subreddit, and it’s clear that this initial release doesn’t yet have the makings of a continuously popular co-op or multiplayer title – despite launching after several delays and with a full schedule of live service ‘content’ lined up.

The curse of any great game is that making a worthy sequel is almost exponentially harder – you have to hit all the same high points as the original, while also changing enough to justify the new numeral. 25 years after the original Homeworld and 22 years after the (weaker) second mainline installment, Homeworld 3 doesn’t hit that high bar to eclipse its predecessors and become the new best Homeworld.

That’s not through lack of effort, or lack of imagination – the vibes here are pure Homeworld, the switch to denser environments is an interesting twist and I genuinely enjoyed nearly every moment of the 10-hour campaign. There are just a few development decisions, made too early or too late, that bring down the experience.

Some issues, like unit compliance, frame-rate struggles, small maps and the barebones roguelite mode, ought to be fixable and have already been the target of post-launch patches. Others, like the storytelling, are probably too deeply entrenched to be anything other than lessons for the future. And I do hope those lessons will be taken to create another new Homeworld game – it’s clear that Blackbird Interactive is a capable steward of the franchise, and with fresh fan feedback, they ought to be equipped to create something with the potential to equal the best of this beloved series.

A copy of Homeworld 3 was provided for review by Gearbox Publishing.

Add comment