For years, a dangerous and charismatic game has evaded the grasp of many designers. Some say it doesn’t exist, that no publisher would ever back it. I’m talking about the one city block RPG that Warren Spector has often mentioned. Sure, we’ve seen a few usual suspects already – Deus Ex Mankind Divided, Disco Elysium, even Else: Heart.Break – they all grimace in the line-up but nothing ever sticks. Now, out of the gloom of indie development, comes another perp ready to have his mugshot taken. Shadows Of Doubt is an open world detective sim that comes perilously close to being our guy. Its clothes, stature, gait, and fingerprints match the description of what Spector often describes. And yet, if you tilt your head, something is just a little off. The game isn’t confined to one block. It’s not an RPG precisely. And its simulation has plenty of bugs, jank, and unintentional comedy. But after all this time, in the absence of a smoking gun, shouldn’t we just put this guy in the slammer and call the case closed? I say yes, let’s. Officers! Arrest this game, it’s brilliant.

Shadows Of Doubt is not only a simulation of a fully working, sleeping, and murdering city, but also a simulation of the paperwork and footwork required to solve those murders. It generates a whole city and sends its countless citizens around on their day-to-day routines: work, home, the bar, a diner, the local arms dealer in a grotty basement. You know, normal stuff. As a result, it is complex, ambitious, sometimes broken, often funny, and limited by its own lofty goals. I’m very smitten with it.

You play a private detective who walks the streets, sometimes accepting small time investigations (side quests) to recover lost items or find missing persons. But mostly taking on longer murder cases. Bodies are often found in their own apartments and it’s up to you to find out what happened.

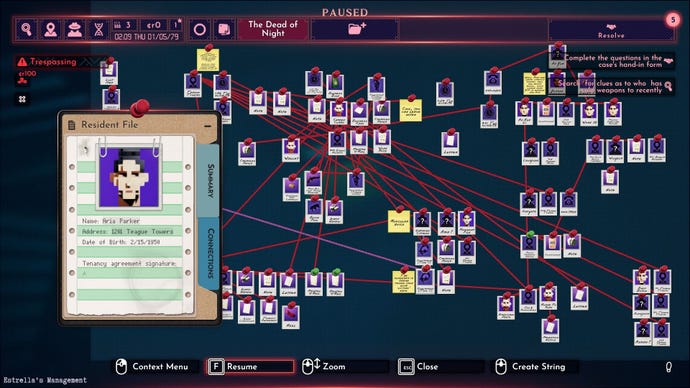

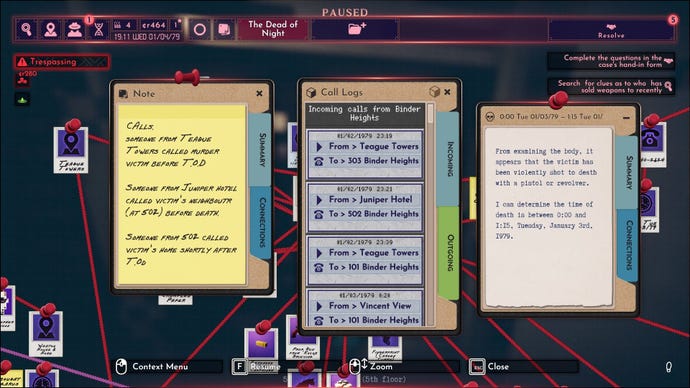

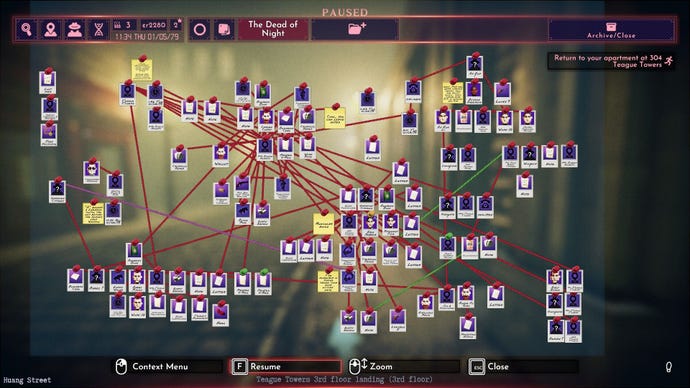

What this looks like, in videogamey terms, is a first-person walkabout in which you pick up a lot of items, wondering if they’re clues or not, and glaze a lot of surfaces with a fingerprint scanner. Much of your time is spent looking at a corkboard (a screen you can summon at any time) where you can pin information, like a gurning butterfly collector. A photo of the victim, a phone number that called that fateful night, a letter he was sent by an insurance company, a snapshot of the bullet casing found next to his corpse. Poor sap didn’t see it comin’.

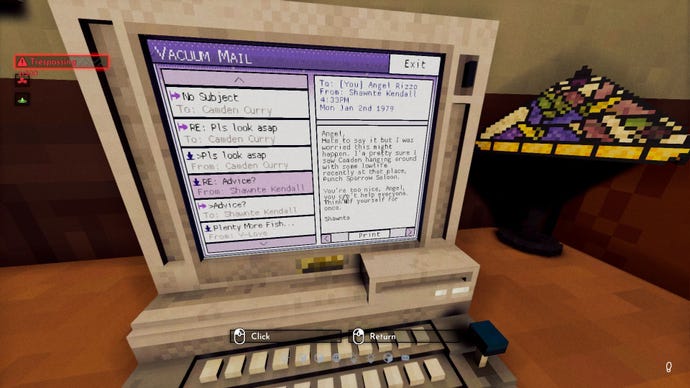

This case board is the first sign that the game is secretly about what I’m going to call “fun drudgery”. There’s a lot of unglamourous paper shuffling. You routinely have to finger through employee records in an office (often by torchlight after breaking and entering). You’ll sift through paper contracts and computer files to check individual records for a clue on each person’s shoe size, or body type, or date of birth.

Even to “resolve” a murder, you have to fill in a form at the city hall. You’re asked for the name of the killer, their full address, a credible murder weapon, and proof they were present at the scene of the crime. This is the information around which your investigations orbit, the essential ingredients of a cracked case. It reminds me of board games more than video games, sharing the objectives of Cluedo, and the piecemeal information gathering of Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective.

So, a game of blood and paper. Sounds quite orderly as murder mysteries go. Perhaps it is, for some detectives. In my experience, as detective “Dick McClumps”, it’s often a wonderful Coen brothers farce.

My first case saw me visit a luxury high rise, where I was marked as “trespassing” just for dripping my raincoat on the marble hallway (you can get fined if you’re caught). I was in a haste to gather dirt on a person I suspected of buying a weapon on the black market. In my hurry, I broke into the wrong apartment. The suspect was next door. “That’s okay,” I thought as I realised my error. “There’s a vent shaft in this closet. I’ll adopt the usual immersive sim tactic, and crawl next door via the air ducts! Hah!”

Foolish McClumps. You see, Shadows Of Doubt doesn’t just offer a simple pre-designed path of venty tunnels between significant locations. This is a fully simulated city. All places may be significant. Ergo, the entire building has a vent network. Do you know how hard it is to find your way around inside a warren of identical metal tubes? Also, vent shafts on the 17th floor of a skyscraper are freezing, meaning a negative status effect that hinders your movement. I got so lost, I emerged into yet another innocent person’s home. They found me standing in their kitchen, shivering, and they chased me, like a cockroach, back into the vent. By the time I found my way back out into the building’s lobby, I decided to call this entire lead a write-off, and go warm myself by a barrel fire in the street.

Experientially, this whole sequence – a result of the game’s intertwining systems and commitment to simulation – was more interesting, funny, and unique-feeling than many first-person explorathons I’ve played in recent years. And all I did was pick the wrong lock and get lost in a vent. In terms of “emergent gameplay” Shadows Of Doubt is an incredible toy. It also fits into the quiet trend of “knowledge-based” games that encourage active learning as a means to progression, as opposed to “hey, you can double-jump now!” (Although there are biomechanical skill upgrades you can unlock).

My role-playing of hapless investigator McClumps would continue. I found myself following a peculiar trail of milk cartons, deeply paranoid that someone should drink so much damned milk (it came to nothing – people just like dairy). I tracked down one killer and snuck into her home, creeping under her bed to look for the murder weapon. Suddenly, the killer’s partner came into the bedroom, climbed into bed, and started snoring. At any time you can check your watch to see the in-game time ticking by. I was stuck there for an hour.

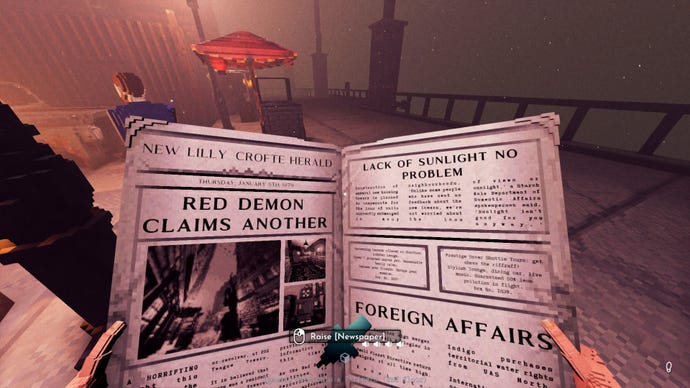

That particular case ended in a round of fisticuffs – a rudimentary biffing mechanic that was absurd and hugely entertaining, yet definitely a type of movement the game doesn’t feel well-suited to. Inventory management and item use is likewise a fiddly, game-pausing affair of pill-swapping and lots of clicking on “drop/place” with inaccurate results. These foibles didn’t bother me so much, but I know it’ll drive some people up the wall. I only appreciated how the limited inventory space would force me to make silly choices. At one point, I threw a revolver I’d confiscated into the river, just so I would have room in my pockets for a newspaper (you can use it to hide your face and it sometimes contains information about the murder cases you’re on).

So there’s your fair warning: this is a fully simulated toy of murder mystery, but a slightly wonky one. Between its many systems, crossing one another like red string on a corkboard, lie a lot of weird, glitchy knots. While stealthing, people will lose sight of you or spot you without clear reason. While staking out apartments, I saw folks regularly come out of their homes and immediately re-enter, as if they all had the same habit of forgetting something. People in the street can be randomly sensitive to your presence, often accusing you of following them when you really couldn’t give a tuppenny shit. By contrast, office workers don’t care one jot if you occupy the same seat as them to use a computer while they’re already on it. I sat in the lap of a company receptionist, printing out employee records one after another. He said nothing, and I suspect he enjoyed it.

Some will fairly consider such jank a flaw in the simulation. Anyone complaining that 1.0 still feels a bit “early access” is justified. But, having smiled or laughed at many of the oddities, I feel many flaws are also part of the game’s ambitiously layered texture, the price to pay for a deeply complex and truly emergent game. You will run up against the limitations of the game’s world, absolutely. Emails will repeat, you will see patterns and murder types emerge, as if finally noticing a texture tiling into the distance. But for a game to be as anecdotally rich as this, I can forgive the repetition, the sight of its seams.

For a closing example, take chatting to NPCs. It’s a classic case of dialogue being more or less identical for every person in this world. You’re offered the same menu of questions to put to every person, and usually get the same variety of bottled, non-descript responses. This rings a bell. Mount and Blade‘s dialogue was similarly systematised, a vaguely human set of sentences and concerns that repeated themselves across all cultures and characters.

Just as I clicked through those samey menus seeking marriages and mercenaries, I eventually accepted the identikit witness testimonies of these cyberpunk citizens. Yet what I happily accept as a systematic (and funny) punchcard of chit-chat may snap the atmosphere in half for other players who crave a greater sense of humanity. The monolithic voice of the citizens can be an alienating force, a reminder that this is a machine, a sim, and not a living place. This is probably not the “one city block” game Warren Spector sorely seeks to detain, in other words.

Yet in all its clockwork detail, I admire it all the same. Buying into its world, bugs and all, has yielded the satisfaction of cases closed and the comedy of killings that completely stumped me. It took me 9 hours just to find the killer of the tutorial mission. For in-game days all I had to go on was an initial – A. Then for more hours, only a first name. After endless dud leads, dopey mishaps, and one bullet in the back by a security guard who found me snooping in her office, I finally found a surname and address for my suspect. I gasped a zealous “gotcha!” at my screen, and understood that something about Shadows Of Doubt felt special. It might not match the prints of the grail-esque single city block. But I think the immersive detective sim has found its first true killer.

Add comment