A true puzzle classic is explored in this gorgeous documentary compilation.

The story of Tetris is pretty well known by now. There have been books and documentaries – foremost among them a wonderful BBC doc called From Russia with Love – and there have been movies and YouTube histories and all that beautiful jazz. And yet what I adore most about Tetris Forever, a new playable, interactive documentary from a team that has already shown it’s very, very good at making playable, interactive documentaries, is kind of perverse. What I adore most are the moments that Tetris Forever steps away from the familiar story, the familiar falling shapes, the familiar talking heads and talking points, and makes Tetris feel really weird again.

Case in point: Hillary Clinton, first lady of the US on a plane in 1993 playing Tetris on the Game Boy. It would be a stellar picture in any case – a private moment extracted from a very public life, the mixture of deep concentration and relative frivolity, the neatly buttoned coat and just the hint of a smile of satisfaction forming. But knowing it’s not just the Game Boy, but Tetris on the Game Boy somehow makes it all the weirder. Worlds colliding. You, Tetris? Here? Really?

Another case in point: Tetris was the first video game to have been played in space. 1993 again – a big year for Tetris, it would seem. Nintendo’s Howard Lincoln gives a Game Boy and a copy of Tetris to cosmonaut Aleksandr Serebrov, and he dutifully plays it in orbit. Doesn’t that feel bizarre but also just right? Tetris out there, ringing around the music of the spheres? The essential, inevitable video game in an environment defined in such stark, timeless fashion by Gagarin and Kubrick?

I didn’t know that about Tetris and space, although if someone had asked me, hey, what do you reckon the first game played in space was, I would have said: Tetris, for sure. But that’s the joy of what Digital Eclipse does. Tetris Forever is the latest in the team’s Gold Master series, in which video game history is treated as video game history should be treated. Attention is lavished on it. Lots of it is interactive and genuinely playable. And even before all that, the curation is exquisite. Previously we’ve been given Karateka and the birth of the cinematic impulse in games. We’ve been given Jeff Minter, a genuine creative genius. And now Tetris, the forever game. The game so deliriously simple and compulsive it still feels like it was discovered as much as invented. That’s not to take anything away from its creator, Alexey Pajitnov, just as revelling in the laws of motion doesn’t take anything away from Newton.

So yes, you get the story of Tetris’ creation in a computer lab in Russia, and the shenanigans as it made its way west conquering everyone who played it. There are flyers for delightful oddities, like a Tetris arcade game with massive controllers, and pictures of the time Tetris was played on the side of a building. There’s a lot about the attempt to sequelise or build upon Tetris, much of it playable: Tetris 2, Hatris, Bombtriss. And all of this is bravely eloquent, because these games, while fascinating, cannot come close to inventing something fresh that competes with the original. And so? And so clever people either add new tweaks – the hold button, soft- and hard-drops, Ultimatris! – or they engage in weird variations and mutations. I love this stuff, and here you can play an awful lot of it.

Caveat: the two versions of the game you might be expecting to lurk at the core of the collection are not present. You can’t play the Game Boy Tetris here or the version for the NES that Nintendo made, whose rounded, hard-candy pieces are forever stamped on my brain. I miss these versions – just as it would have been a serious coup to include the legendary Tengen take on Tetris – but there’s more than enough other stuff. There’s the version of Tetris for the Apple 2, I think, which I first saw when I was a Russian language student staying in Moscow for a week in the 1990s. There’s Bullet Proof’s take on Go for the NES, which is filled with delightful little design elements, and there’s Bullet Proof’s version of Tetris for the NES, which I had never played before and which, as an actual game of Tetris, feels delightfully wrong in a way I can’t put my finger on. There’s Tetris Battle Gaiden, a multiplayer affair that is much loved in the Tetris community and which I had never had a chance to play until now.

More than that, though, there’s a brand new variation, called Tetris Time Warp, which throws in special pieces with every ten lines cleared, and these special pieces blast you back in time to a different version of Tetris that you hack through for a bonus. Better than working brilliantly – and I mean this as a high compliment – it sort of works. It’s a wonderfully elbowy, awkward cludging together of slightly different experiences. It feels like one of those science fiction movies where people slip back and forth between dimensions. It’s Tetris: His Dark Materials.

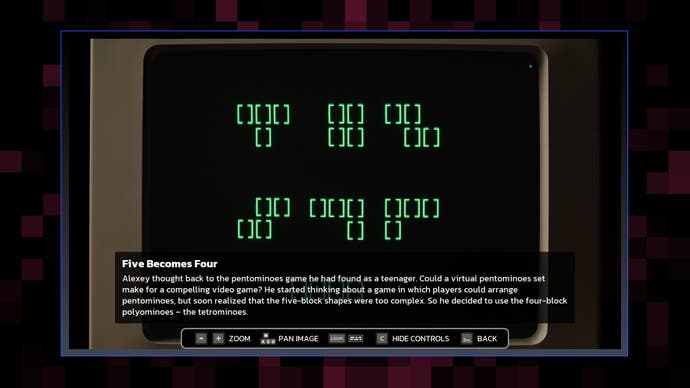

And then there’s the final great version of Tetris, the one at the heart of the collection. And it turns out to be the first version of Tetris. It’s a recreation of the original Tetris, back when it ran on the Electronika 60 and the blocks were made from brackets. It’s a joy to play – you really get the sense of vast, unstable tech, the kind of tech that makes the lights flicker when you turn it on, running the whole thing. And you really see afresh that Tetris was pretty much born perfect. The decisions Pajitnov made to get it to this point seem complex and idiosyncratic – four-block shapes not five-block shapes, new blocks dropping in rather than a set handful to simply be arranged like puzzle pieces, completed lines killed off to keep the space playable – but the end result is…well, it’s natural. It’s eternal. It’s unnaturally natural. It’s the game that someone, something, will be playing somewhere when the sun explodes. It’s Tetris.

A copy of Tetris Tetris Forever was provided for review by developer Digital Eclipse.

Add comment