This return to Alan Wake’s horror roots feels a little lacking compared to the main game, but its examination of AI and art’s relationship with science arguably hides its most daring meta commentary yet.

After its joyful romp through the multiversal lens of its Night Springs DLC earlier in the year, Alan Wake 2 rounds out its pair of story expansions by going back to what it does best: dialling up the horror, switching off the lights, and having all manner of shadowy ghouls lurch out of the darkness to give you a good old scare. In The Lake House, FDC agent Kiran Estevez finally takes us beyond the chain-link fence of Cauldron Lake’s most secretive, walled-off area – the titular research lab where inside its brutalist, concrete depths lurks an experiment that’s gone terribly, terribly wrong, and threatens to cause another catastrophic event that could spell disaster for the nearby town of Bright Falls.

But despite taking place before the events of the main game kick off in earnest, both the setting and its new protagonist almost make The Lake House seem more like a warm-up for Remedy’s Control 2 sequel than it does its Alan Wake namesake. This three-hour excursion into the lab’s dark, paint-splattered hallways is a mostly tense and spooky affair throughout, but one that feels a little bit lacking in what made Alan Wake 2 so special when it came out last year – namely, it has a lot more in common with Saga’s more pedestrian side of the story than it does with Alan’s reality-bending writer’s board sequences.

This is no bad thing in and of itself, and it’s a perfectly enjoyable standalone set piece for those who have already bought into the game’s expansion pass. But when you take it all together, with its surprisingly sparse number of enemy encounters and a veritable truckload of story exposition delivered through film reels, computer emails and audio log diaries, it can’t help but feel like you’re only getting half the Alan Wake 2 experience here. It’s missing that climatic rocket punch to really give this bold and ambitious game the final, showstopping flourish it arguably deserves – the aural and visual pièce de resistance that ties it all together and leaves you in little doubt that Remedy is a studio at the height of its power. You want Alan Wake 2 to go out with a bang, not a whimper. But for me at least, The Lake House often simply fizzled rather than igniting something deeper.

Kiran herself is a very affable presence. Her no-nonsense sarcasm and dry wit make her feel just as capable and fun to be around as Saga did in the main game, but she also has moments of vulnerability that make her highly empathetic as well. It gives her a winning, every-woman kind of quality that allows you to really buy into her ominous retelling of events via voiceover that this is going to be one terrible day at the office.

With the Lake House lab seemingly abandoned on arrival, the main thrust of Kiran’s journey takes the form of obtaining ever-higher security clearance cards in order to penetrate the lower, more dangerous levels of the facility. As she makes her way down each floor, you’ll need to employ some light deductive work to restore power to certain areas, get into various locked doors, and – once or twice – alter the nature of reality by using Control’s power core switches to get past obstacles. In Alan Wake terms, the latter are pretty much identical to Alan’s lightbulb lamp, as getting a core from one location to another and flipping its nearby switch will blink new scenery into existence, opening up new pathways that were previously blocked off. If only it relied more on these puzzles as the expansion went on. Alas, they’re used so sparingly, and are so painfully easy to execute, that they barely feel like puzzles at all.

Worst of all, there are great swathes of The Lake House where all you’re doing is wandering through empty corridors with little to no threat on show to spike your adrenaline. There’s a lot of document reading, a lot of poking through empty drawers looking for ammo and supplies to prepare you for encounters that never seem to materialise, and there were several moments where I kept wishing something, anything, would happen. Like the main game, the sound design and mercurial visual effects do a lot of heavy lifting to keep players feeling tense and on edge, but outside of its clearly telegraphed fight sequences, it doesn’t take much for that uneasiness to start slipping away, its blasting horns becoming little more than irritations that you wish would pipe down just a notch while you read this important case file.

To its credit, there is a lot to poke around in inside the Lake House. One floor, for example, is entirely optional, a warren-like maze of library archives that has no real bearing on the overall story, but which contains a vital tease for what Remedy is cooking up next with its Connected Universe concept. Likewise, there are several high-clearance rooms on other floors you can return to for extra background lore if you wish, but which also aren’t essential to reaching the end credits. Even within its tightly defined concrete walls, it’s a much more freeform setting than any of the places we visited in the main game, and Remedy heads will find plenty to luxuriate in here – though having read and listened to everything on offer here myself, a fair amount of it felt like it had been repeated elsewhere in the facility beforehand, and only some of it really shed new light on what was really going on here.

What is going on here, though, is kinda absolutely fascinating to me. At once a meditation on the dangers and use of artificial intelligence in the creation of art, and the folly of trying to scientifically quantify the creative process, reducing that raw, unknowable spark of emotion to numbers and units that can be measured and predicted on a graph, the underlying arc of The Lake House is a shot of pure Alan Wake meta commentary at its most indulgent. Some will no doubt find it overly pretentious and obnoxious, instantly lumping it into that same, cringeworthy bracket as the original Alan Wake and its supposedly poorly written pastiche of what constitutes modern day crime writing. But this is also precisely the reason I kind of adore Alan Wake 2, as it was Saga’s sections and her infinitely more natural mode of storytelling that exposed just how deliberately bad Alan Wake’s writerly narration really was (though I’m sure the decade-odd gap between each game also helped Remedy’s writing team mature a bit in the interim, too).

For me, Alan’s clipped and overblown writing style is an intentional and considered choice on Remedy’s part, and it’s something that really gets put under the microscope as The Lake House unfolds. Across two games, we’ve all seen the impact Alan’s words can have on his environment, and the head scientists heading up the Lake House lab are utterly enthralled by it as well – even if one of them believes that paintings can harness the power of the interdimensional rift residing at the heart at Cauldron Lake much more effectively than Alan’s books. As each competes to refine their work via live (and unfortunate) human test subjects, a schism starts to form between the powerful precision of the written word and the open, more interpretative nature of traditional art.

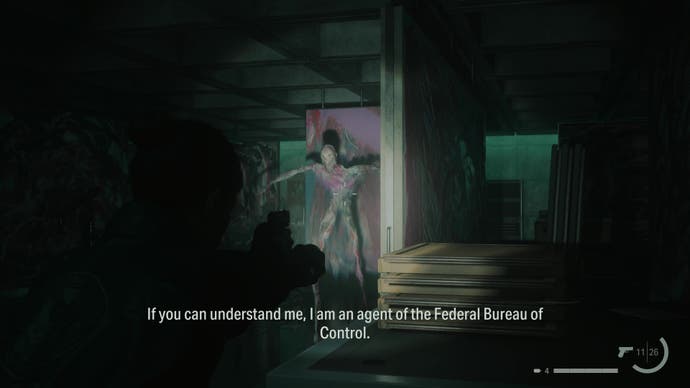

Admittedly, the paintings don’t quite do it for me. When Kiran arrives, the artist at the centre of this story has already hit the angry, abstract phase of his career, giving us little to hold about how the use of his paintings may have changed over time, and the monsters that emerge from like walking, pastel oil slicks are sadly quite one-note – if only because all you can do is run away from them for the majority of the expansion due to your FBC weapons being totally ineffective against them. Maybe it’s a symptom of its truncated run-time, but it never feels like Remedy quite gets its arms around what makes these paintings different to Alan’s writing, and how they might affect change in the world in a way that feels unique to the medium.

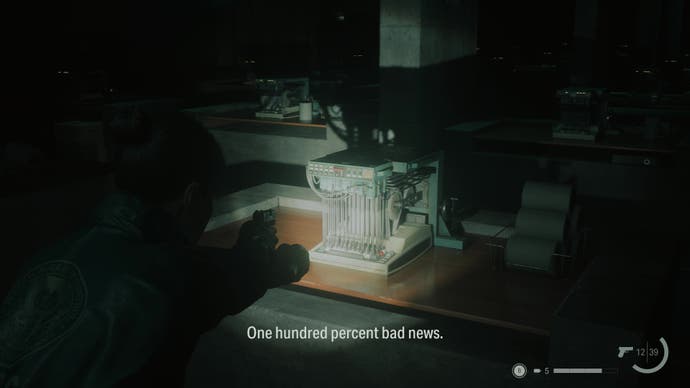

Alas, we don’t ever get another taste of the Alan side of this research project – with the man himself obviously missing in action, The Lake House, too, suffers from his absence. That said, when one team of scientists resorts to trying to recreate his work scientifically, analysing the subject matter, content and number of words per sentence so they can feed it into a special automated typewriting machine, it does build to one of the expansion’s most eerie and memorable set pieces. Try as they might, however, they just can’t quite nail Alan’s style, and the increasing desperation that both of its lead scientists feel at failing to make their own respective ‘creative’ breakthroughs bleeds through into every part of the game – from the exasperated film reel diaries, the increasingly passive-aggressive email chains on their computers, and the whiteboards filled with questions and frantic scribbles. The tension between these two antagonists is as palpable as the menacing and possessed staff members that now stalk the halls in their wake, and they make for a great pair of villains.

Of course, it would be a complete and total cop-out on my part to come away from The Lake House and just say, ‘Well, maybe it’s meant to be a poor imitation of the main game because that’s the whole point it’s trying to make about AI and the quantification of art’. That would be a pitifully poor excuse for waving away The Lake House’s underlying missteps, to say nothing of just how unthreatening its new paint monsters are, nor how woefully underutilised its similarly novel (and frankly incredible) Ghostbuster-style paint-busting rocket launcher is. Why does it not go harder on all this stuff to make it feel more distinct? Instead, it simply opts for what’s safe and familiar most of the time, and never quite reaches those same, dizzying heights you know it can.

In another reality, though, you could also see this being exactly what The Lake House was, indeed, going for all along, and there is a little part of me that quietly respects a game that might feasibly knobble itself creatively, just so it can stroke its chin a little bit longer and carry on its own internal conversation with itself. It would be daft in the extreme, but also so utterly in keeping with the Alan Wake-ness of it all if that was actually what Remedy was choosing to do here. Because let’s face it, if it’s willing to parody the candy-cane fantasies of a Mills and Boon romance, the weird fiction and inane lore of its own in-game coffee brand, and the surreal, temporal meta of actors and creators in a game of a game of a game – as it did during each episode of its Night Springs DLC – there’s a sense that nothing is ever really out of bounds for Remedy when it comes to Alan Wake. And I love that it’s a game that could even entertain such a dumb and preposterous notion like this. It’s the reason Alan Wake and the Remedy Connected Universe will always be a subject of fascination for me, and why The Lake House – while flawed and inconsistent – is ultimately somehow still a fitting end to this singularly giddy and bananas horror story.

A copy of Alan Wake 2’s Deluxe Edition was provided for review by Remedy Entertainment.

Add comment