Explore a bright vision of subterranean nature in this astonishingly rich Metroidvania.

In the dripping midnight glade there is a telephone resting on the earth. It’s an antique. I can tell that from the limited 2D pixel art. Although it’s just a few lines and dots and smudges of light, I can imagine the weight of the receiver in my hands, almost feel that strange matte chill of the Bakelite.

The telephone is important here in Animal Well. It’s how you save the game, for starters. But the more I have explored, making those long looping journeys left, right, up and down, the more I have found myself heading further out in these directions than I had assumed was possible, and the more I worried that I had left the actual game design behind and was moving through a landscape of personalised glitches and oddities? The more I did all this, the more the sight of another telephone came as a sweet relief. A save point, yes, but also a sign that someone had been this way before me. A sign that even as I navigated bright mysteries, I was still on the right track.

There’s more. The telephone is also a sign of a second world imposed on the first one, of technology, communication, cablings and wires and electrons, of messages buzzing through an artificial network threaded into this glade and into this world of trees and grass, rock and ruin that lies beyond it. If you’re trying to understand Animal Well, to get to the bottom of it – good luck with that one by the way – or if you’re trying to just get even the slightest grip on this game’s dense, intriguing, endlessly playful and engrossing world, the telephone is probably a good place to start.

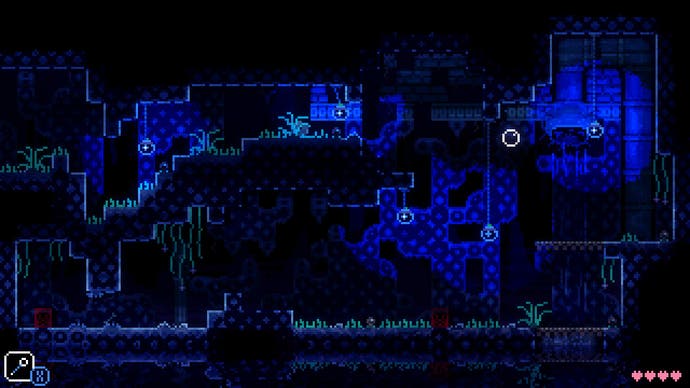

Animal Well feels like nothing other than Animal Well most of the time. It feels like a game built of mysteries and strange rituals, where you’re a stranger granted the freedom to poke about as you please and follow your own threads. But I guess on some level it’s a Metroidvania. It’s richly peculiar from one moment to the next, but it’s also a game of gates and gear. You start, a friendly little lump sat amidst subterranean wilderness, at the very middle of a map that is all but lost in shadow. As you explore, you make complex journeys in every direction to uncover more of this place one room at a time, before discovering that somehow you’ve come back to the start, but with fresh options.

Gear and gates! As with all Metroidvanias, you gain access to new routes in Animal Well through the gadgets that you find. I’m not going to spoil any of this, not even the basic gadgets. This isn’t because I’m lazy and ducking an explanation, but because this stuff you pick up is always an unlikely object that has an initial delightful use, before it then reveals itself to have multiple other uses, all equally delightful. These additional uses suggest themselves as you examine the puzzles you are faced with, as you push against the world’s apparent impossibilities, and as you develop your powers of simply imagining what else your tools might do. Sounding out these gadgets at such moments, you’re pondering what else is logical and practical within them, and what else lurks just beyond the realm of ordinary thinking. There is such pleasure here when you uncover a new use for an item you thought you already knew inside-out. The instance of the finger post! It will be a revelation, which gains its power through the fact that, looking back, it was all so obvious!

That’s Animal Well. And the game’s 2D world often opens out without the gadgets, too, as you simply start to understand how the game works a little better. You’ll work out where the game likes to hide secrets, and how it broadcasts the crucial differences between one kind of wall and another, and you’ll learn to spot something you have learned to notice elsewhere in the map, and then capitalise on that. I will give you one example, with the gadgets removed so it’s a treat for you too when you get there. At one point in the middle of the game I stood on a subterranean shoreline and realised that an architectural feature I was faced with, half-buried in the water, often came with a separate mechanism that I could manipulate. And maybe that mechanism was here, too, but hidden from view by the environment.

That was a huge moment for me. A real victory. I wanted to write postcards about it to friends I had not spoken to in years. But here’s the thing: it felt so particularly good because, even as I worked out how to manipulate this potential mechanism, I already knew it would work. I was certain. I had briefly joined minds with Animal Well and its creator.

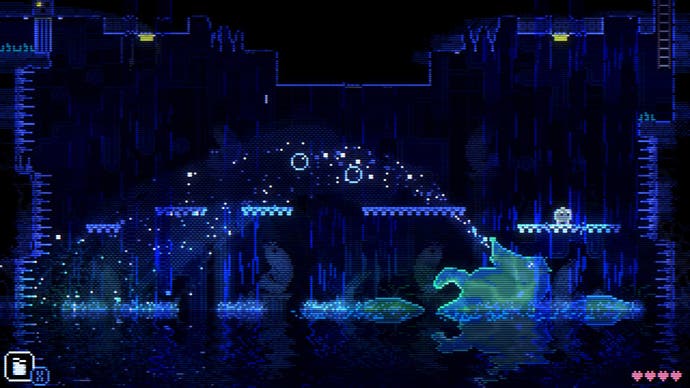

I can risk that kind of spoiler because Animal Well’s worlds are filled with revelation and moments of smart pleasure. The game takes you through beautiful caverns, one screen at a time, and even before you get to the creatures, the wildlife is a real source of astonishment. This is pixel art, which suggests nostalgia and throwback aesthetics, but there’s something very new about the way it is employed to create streams and lakes, or to set a torch swinging on a chain, or spring creepers from the ceiling that brush aside gently as you move by. One room might be a maze dug through the damp soil. Another might have the remains of the gate for an old house. My favourite is just an elbow of downward-dropping tunnel in a sea of black, with a single lamp hanging from the ceiling, its red light scattered and scumbled by a waterfall.

Those animals you encounter, though. Large and small they never feel like they’re purely there to help you solve a puzzle or to lead your eye. They’re there because this buried world is their world too. Deer graze. Birds hang back and watch for an opening. Some of the larger beasts just eye you from a distance, amused. They bring a sense of occasion to certain moments: what a Naughty Dog game would do with a swell from the orchestra, Animal Well will achieve with a row of storks stumbling quietly from left to right across the screen – a march or migration that you have just chanced across, that speaks of a world with its own concerns beyond your concerns. You’re not the hero anymore, you’re a bystander, and it’s brilliant.

Even so, the game is clear and focused in its puzzles. Many of them fit into a single screen at a time, giving you something to ponder, a taste of victory, and then a ritual as you move on and find the next room and the next puzzle. Some, though, spread across multiple screens and multiple environments. Often it’s doors and keys and corridors and switches, along with dead ends that are not as dead as they seem, but there are no cheap throwaway puzzles here. The simplest will encourage you to use one of your gadgets in a thoughtful way. The more complex will encourage you to use three or four gadgets, to break a solution into beats in a sequence, to utilise timing and platforming skills.

What a world to explore. Animal Well’s landscape is dark, but it’s a wonderfully stagey kind of darkness, slightly unreal, slightly theatrical, filled with expectation and potential. There is something of watching a theatrical play at work in this game, the awareness of something very live and human intermingled with artificiality, performance threaded along with blacklight tricks, the shifting flats that roll back and forth.

And it all serves a purpose. The reason I’m being so coy about the specifics here is that thinking about how to capture this game without simultaneously spoiling it actually led me to a fundamental insight. Other games have discoveries in them. Animal Well, like Fez and Tunic and a handful of other sublime delights, is discovery. It’s discovery right up to the end and far, far beyond that. It’s a game that wants you to keep on going. I will be pondering parts of the map for months, wondering what I missed, what I couldn’t imagine.

Anyway. I read a good Tweet recently, and of course I didn’t save it, that talked about the difference between old episodes of The Simpsons and new episodes. The Tweet argued that the reason the old episodes were so great is that the people who wrote them had been marinating for years in all kinds of weird old media, while the people who wrote the new episodes had been largely marinating in The Simpsons. I have no idea whether that’s true or not, and I have no idea if something similar holds for Animal Well. But I mention it because the things this mesmerising, maddening game seems to evoke, the things it seems to have emerged from, strike me as being so singular and odd and rich and well chosen. There’s something of Jet Set Willy here, and his strange impossible house. It’s there in the screen-by-screen puzzles and challenges, in the black backdrop, in the love for suggesting depths and context that are not always fully present. And there’s something of nature writing in all those perfectly observed pixel art squirrels and fish and deer, doing their animal things in their own habitats, creatures that have been observed and then recreated with patience and insight and character.

I often fall in love with games, but Animal Well is slightly different. I’m astonished by it. Astonished by the ease with which it presents its ideas, the joy these ideas bring, and the sheer range of magical stuff it includes, all clipped together in such a satisfying manner. And fittingly, for a game about wells, I am astonished by how deep it all goes.

Review code for Animal Well was provided by Bigmode.

Add comment