“We are a people who honour democracy,” said the dog, scratching himself. “Per our custom, you may drink of our fresh water.” The dog was called Senator Umeshefaat, and he was very civil, even if he was shedding his black and white fur everywhere. We spoke in his home village at dawn. Later, I examined the senator’s personal history more thoroughly and discovered he was “hated by bears for cooking them a rancid meal.” I suppose every politician has their enemies.

That Caves Of Qud creates fun anecdotes out of simple encounters shouldn’t be a surprise. It has had 15 years of early access to establish itself as a small-but-mighty story generating roguelike of repute (there’s a reason it sits deservedly side-by-side with Dwarf Fortress in the same publishing house). After creating many characters, and dying and dying and dying again, I understand why it grips the brain with such fierce glee. It is a machine of grand imagination and adventuresome comedy. A deceptively powerful RPG that isn’t half as obtuse to newcomers as the screenshots make it out to be. Qud’s low-res bark is just a complement to its bite.

That said, if you’ve not played many classical roguelikes before, it may still appear intimidating. You can play with the mouse, clicking on locations you want your character to go, and navigating menus with taps of the cursor, but it’s really designed to be entirely keyboard based, clacks of the numpad and plentiful hotkeys summoning to mind days when mouse pointers did not even exist.

For me, that’s easy to get used to. For all its complexity, Qud at its most basic is a straightforward game of walking around, revealing the map with each step, and directing your little warrior into the nearest angry lizard. Approach it both as a grand sci-fantasy epic and as a dry, knowing comedy. The tone is exemplified by the game’s tutorial, which sees you emerge from a training cave into Joppa village. “Everything you learned in the cave applies here too,” it says reassuringly. “Villages are like caves with very high roofs.”

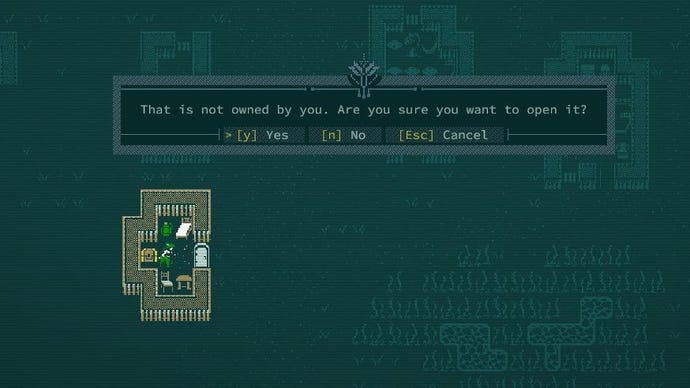

If you can get the simple rules of movement and combat, everything else will follow. For long-toothed roguelikers this won’t be hard, but I want people who’ve never played something like this to also reconsider their doubts. It’s got a lot going on, yes. But nothing moves unless you do. Nothing will hit you until you take a step yourself. You can look around and examine all items, monsters, and tiles around you with a tap of ‘L’. In its pause-by-pause way, the traditional roguelike is a hugely forgiving thing.

Until, of course, it is not. A sign of quality in games can sometimes be divined in the variety of its deaths. “You were frozen to death by an ice frog,” I am sometimes told by Caves Of Qud. “You were killed by a chaingun turret.” Most downfalls are the result of violent encounters with hostile creatures, as you tap your character in their direction, hoping for a lucky melee strike. But there are other ways to triumph over enemies than directly bashing them with a mace in each of your four mutant hands. Talk to them? Sure, try it. But also: fire muskets, throw grenades, rend minds with a mental attack. A lot of the time death will come in the form of a desperate final button press towards (or away from) your foe. It will often go badly. “You were bitten to death by Bakabobukubuyuboo,” I have been told, “the renowned honey-loving bear.”

There is no end to the perishing, with demises ranging from the mundane to the extraordinary. I once got lost in a winding canyon for thirty minutes, only to be impaled by a non-descript chameleon that caught me off-guard. Later, I was gas-bombed by my parallel universe twin, aka “salty bloody evil Borkubine”. He’s “salty” and “bloody” because we got into a knife fight in a mound of rock salt, and both of us became covered in the stuff. He’s “evil” because he is not me.

In that life, I was playing as a quill-covered, multi-limbed spiderfreak I named “Borkubine”. You can create your own character, see, mixing and matching an astounding array of abilities (or you can choose from a bunch of presets). I was also making use of the forgiving checkpoints in “roleplay” mode, which let you treat any village as a save point. But in “classic mode”, Qud is more unforgiving and traditional – no skills, items, or riches are carried over when you die, and there is no save-scumming. True to roguelike form, you perish and that is that. You come to value your sharpshooting skills, your investment in armour, or a love for your tactical bubbleshield. Then, in a single lapse of attention, all those shiny upgrades and special weapons are gone.

It elicits a state of tense freedom. In one sense, classic mode makes you want to cling to your fragile life, even if it means acts of bullet-dodging desperation. But seen from the perspective of a nothing-to-lose Rogue diehard, you will find existential liberty in re-rolling a random character just to experiment with new toys and the game’s many “mutations”. (The “Daily” mode is the perfect extension of this, offering the same random start to every player.) Let’s see, what do we have this time? Slime glands that’ll spit toxins? Pyrokinesis? Or perhaps something called “Quantum Jitters” – a defect which will periodically tear space and time accidentally asunder. As lucky dips go, it is a violently exciting assortment of treats.

Mutations are not all combat-focused. An amphibious skin means you are well-liked by frogs everywhere but require two-thirds more water than normal (you also pour it all over yourself instead of drinking it). Photosynthetic skin will let you sate your hunger by basking in the sunlight, instead of eating meals like you normally do. Handy, but then eating food is not in itself a chore. Basic meals are randomly generated at any campfire. The game simply “whips up” something. Tonight, dinner is “a dram of rust, a nip of gunpowder, a terra mung bean, and a contralateral sesame seed”. Delicious.

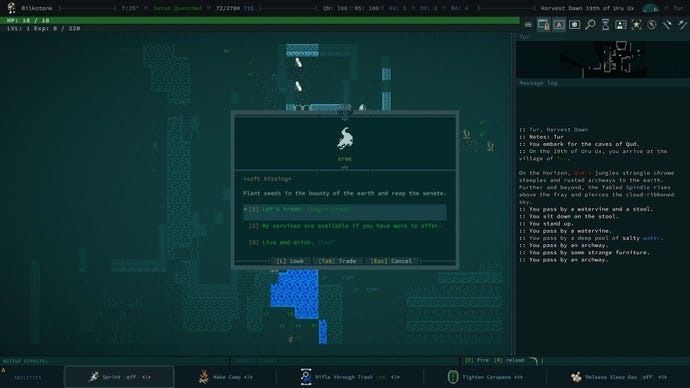

This is just one example of the esoteric worldbuilding that emerges steadily in the messages that gather like layers of sediment in the action log next to your map. This is where you’re told how combat is going (“The bloody snapjaw scavenger misses you with her bite!”) But it’s also a list of all the simple matters of the day. “The way is blocked by a brinestalk wall,” it might say when you bump into a house. “The wet glowfish has nothing to trade,” it’ll inform you when you try to do your shopping in a pond.

For those disinclined to pimply lore, the reliance on reading messages to set the scene may test the attention span. But I feel like Qud’s appearance will already have scared away anyone with a lack of patience for the BBC Micro baroque. It is not really ASCII art, but it does feel ASCII-inspired, the tiny 16×24 pixel sprites sometimes resembling ancient undeciphered hieroglyphs instead of fully realised birdfolk or vine farmers. It is a kind of book-reading magic that Qud does, outsourcing all the heaviest graphics to the player’s brain.

And anyway the actual text is a great example of otherworldly video game language. The kind that has evolved separately to mainstream action adventures with all their cinematic dialogue. “Worms are interested in hearing gossip about them,” you’re told in an exhaustive menu that tracks your reputation with everything on the planet. “Crabs dislike you… You aren’t welcome in their holy places.” There is an expansive and austere comedy in any game that will track your reputation with just about every type of being from salamanders to goatfolk. The merchant’s guild, the water barons, and the villagers of every settlement in the land – these will all accept a “water ritual” as a means of bonding and improving reputation, and will all maintain some opinion of you as you explore, graverob, and offend.

And offend you will, if only because you may not know what you’re otherwise supposed to be doing. Those who crave firm direction in questing may feel adrift at the introduction, a single line that reads: “You embark for the Caves of Qud.” There’s a main quest which is really a chain of quests that don’t always appear to be related to each other (the final parts are the main attraction of this month’s 1.0 release). But they’re still worth doing as a beginner, because they offer a lot of XP to be pumped into unlocking new mutations. And they’ll get you on the loot train, choo-choo-ing all the way to a full suit of ogre fur armour, or whatever equipment is dropped in your game world. One of the more confusing selling points of Qud is its procedural generation. Or to be more accurate, its partial procedural generation.

The game is not 100% random every run. The big world map will always look the same (the salt dunes are always to the west, the spire is always to the north). But at the down-to-tile level of a little guy walking around the countryside, the caves themselves will be different, the loot randomised, the enemy types altered. Villages and other important locations remain the same, but the “history” of the world is random. You can see why things might get confusing. This combo of random and unchanged elements can feel inscrutable, even as it adds mystery and variety.

And what variety. There is a depth and colour I won’t be able to communicate in a single review. You can get lost while you cross the world map, and will be forced to explore new areas to get your bearings. A bloated leech may just as easily be employed as a hired guard (“I’m watching you, traveler”) as attack you wordlessly in a dank cave. Books you find may be called things like “Aphorisms About Birds” or “On the Origins and Nature of the Dark Calculus” or “OPERATING MANUAL FOR LARGE CREATURE” (these are not randomly titled but they are randomly placed and grant XP when donated to a special librarian).

There is a peculiar joy to working out the rules of this world. The game is a mechanism in and of itself. You can fall down a wiki hole about Qud in the same way you can fall down a wiki hole in life. And you will go there in search of answers, without a doubt. But seeing things firsthand before seeking a guide is, for me, a more enjoyable way to discover the world and its rules. I have gotten badly hammered on cave wine, the symbolic spritework of the world getting jumbled beyond recognition in a perfect replication of the sickening dizziness of reading while drunk. I have teleported as an act of desperate escape, only to misfire and appear in a locked room with seemingly no way out (I took advantage of the peace, made a campfire and ate some chickpeas). But my favourite Qud-tale is about a goatman called Indix. Stick with me here – I know this review is long – this is my final effort to convince you that you should play this game.

I find myself in a mushroom village, where a stocky goatman is standing watch. I approach him and say hello. He is known as Indix, the “pariah”. I ask why he’s called that – “pariah”. But he warns me not to ask again. I take the hint and change the subject. I want to be on good terms with these villagers. I am a musketeer. I need any bullets they have to sell.

So I turn to the water ritual – the universal ritual for boosting relationships. After I slurp with Indix, I’m told that “pariahs” the world over now think more highly of me. Unfortunately, all other goatfolk now absolutely hate my guts, just for fraternising with this one excommunicated goatlad. I don’t know why he’s so hated by his people, but maybe it has something to do with the horn that is cut from his head and now hangs around his waist giving him – says the game – “the distinction of being the only warrior to wear his own appendage as a trophy”.

My curiosity is too much. I ask the capricious capricorn why he is a “pariah”. What did he do? Again he warns me not to go there, it isn’t a subject he wants to talk about. No, really, I say, I gotta know. He reacts to my prying questions, let us say, passionately.

I immediately begin sprinting away. It is a wise decision. Hostile enemies are given rankings of difficulty. A dog-like snapjaw might be “easy”, a centipede could be “average”. The goatman is described as “impossible”. I am not doing this today. I don’t have the time to be decapitated by a violent astrological sign of a man who wears his own horn as a belt buckle. I will get my musket balls elsewhere, thanks. As I flee, he works himself into a “blood frenzy” and launches something red and powerful-looking at me. It misses, and I hightail it out of there. I spend the rest of my (short) life hated by all goats, and will later die at the hands of another band of goatfolk who despised me on-sight, all because of this single faux-pas.

This was one funny disaster from one of dozens of lives. Caves Of Qud is as deep as any Bethesda open world RPG (technically 2 billion floors deep) and funnelled through a rich prism of randomness possible thanks to the limited scope of its visuals. It is complex and compelling enough that many glowing Steam reviews are left only after hundreds of hours of playtime. By contrast, I have barely made a dent. Yes, you will have to embrace and decipher the lore-riddled lingo. And you will have to stoically acknowledge infinite death as a means of learning the arcane rules of survival. But persevere and you will discover a realm hundreds of times more vibrant than the dark inky green of its screens.

Add comment