Don’t get too comfortable. As an RPG that puts you in the synthetic boots of an escaped robo-person, Citizen Sleeper 2 often has you on the run. It’s a crunchy, dicey machine of vibrant world-building that sometimes forgets itself in wandering prose. A compelling universe to sail through, with more habitats and hovels than its predecessor, more stations and stellar gateways. It can’t – for me – escape the dense gravity of the first game’s compact storytelling and novel character building, no matter how often it funnels you from one space caper to the next. But it has a good time trying.

Once again you play a “Sleeper”, a biomechanical being designed to work as slave labour. At the start of your story, you are in thrall to a crime boss called Laine, who’s been keeping you under his thumb in exchange for a drug called stabiliser (an injectable pick-me-up all sleepers need to prevent their bodies deteriorating). But here comes a friendly spacepal, called Serafin, who reboots your body and hauls you cold turkey off your captor’s space station. Together in a stolen ship, you’ll explore a belt of inhabited shucks, seeking to put ever more distance between you and the abusive Laine.

The previous game took place on a single rotating station, Erlin’s Eye. But here you’ll gradually unlock a map full of places to jump to, provided you have the fuel. There’s a slender trading spire called the Far Spindle, where a water freighter has ruptured and needs emergency repairs. Or a flotilla of ships called the Scatteryards, where a shipmaker will pay you to paint an advertisement on your vessel. Or an asteroid called the Greenbelt, which grows food in precarious conditions for the whole belt.

In splintering its sci-fi stories into these many small hubs, Citizen Sleeper 2 can feel more sweeping in its space drama. Each place offers “contracts” that send you into a bubble of local space nearby to complete a task, like rescuing lost crew members or salvaging data from a destroyed ship. But it can also feel less deep and more formulaic with each passing hub-hop, too.

Perhaps this is down to the expansion of the game’s more cog-like components. Once again, you’ll roll a bunch of dice at the beginning of each “cycle” (every morning, basically). You slot these into various squares to take an action. Drag a five into working a shift in a “risky” scrapyard, for example, and you’ll probably get paid well and won’t lose energy or accrue stress (two important meters you’ll need to juggle). Slot a one into a “safe” activity, like resting. The twos and threes? Well, those are iffy. But gamble away, work another shift. Why not? On contract missions you’ll also be able to use extra chance cubes provided by your fellow crew members.

But dice can break under certain conditions, making them unusable, or they can become “glitched”, meaning they’ll have a much bigger chance of resulting in a negative outcome. Ideally, you’ll keep all your dice neatly maintained as you go along (you meet an engineer who can gluegun them back into shape). But it’s possible all your dice will rupture in one desperate mission gone awry.

Five broken dice is a tough fail state that puts you on your robot ass and leaves you with a permanent, unfixable glitch dice every cycle. Definitely something to avoid. It’ll mean you’ll have fewer actions every day. Less noodle broth to slurp, fewer cargo shifts to pick up, or perhaps no dice-time to explore dodgy shantytowns spinning in the void. The game’s easiest mode forgoes this punishment, so you can simply carry on the story. The hardest mode doesn’t even humour you. You simply croak it – game over, start again.

That I have to spend this many paragraphs explaining the dice is itself a sign that the systems and item management feel bulkier this time around (and I have not even mentioned “supplies”, class bonuses, dice-altering abilities, or various other currencies). As before, it’s a solid way of giving the story some gamey bones. But this heavier emphasis on the technicalities sometimes feel overbearing.

The more linear hubs especially can feel like there’s only one railroaded way to distribute dice. You simply pump your gambleblocks into the only slots that seem to matter, making it feel less like you’re gambling with story outcomes and more like a forgone narrative conclusion is being click’n’dragged out for the sake of a fancy system that needs to be implemented everywhere. For me, these numerical systems were always less interesting than the characters and stories that orbited them.

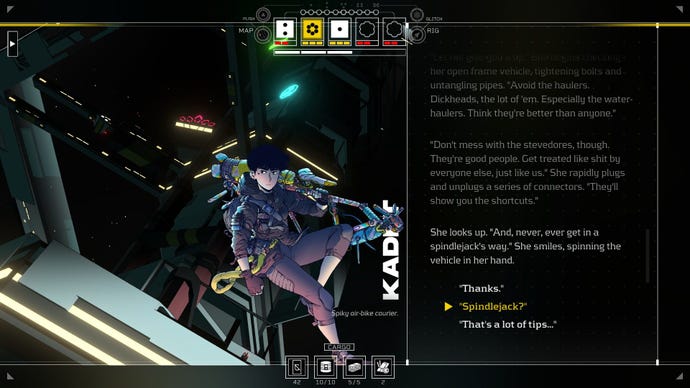

There’s still a lot to like in the people here. The character art has the bright stylishness of a well-inked comic book, soft shadows falling over faces and endless folds of fabric non-fluttering in zero gravity. If you’ve ever bought a concept art book just to see what the artists designed before the modelers got their hands on things, you’ll appreciate the figures that stand against the glowing windows and drifting ships of the 3D animated background.

Crucially, when these characters speak they feel alive. Laine is a heinous pusher man with a slave owner’s cruelty, not to mention a ghostly pursuer whose voice arises in your mind at various intervals. In his eerie desire for total control of your Sleeper’s body, he is a classically dislikable if ultimately diluted villain. Imagine Kilgrave of Jessica Jones poured into a glass with a spritz of Harvey from the 2000s fugitive sci-fi show Farscape (a show the game’s creator cites as an influence). Laine is a systemic stressor as much as a storyful one – a little red clock often ticks down when you’re exploring a hub, to show that he is on your scent. You will have to get out of dodge before he arrives.

There are other memorable folks. Nemba is a straight-talking chef who might fire you from a part-time gig in his kitchens, but only because he has a cheeky side-mission in mind. Kadet is a leatherclad space biker who coolly saves your life from a cargo hauler, then uses her biker chick charisma to rope you into dodgy data dealings. There are a lot more examples of such characters. But what unites many is a sense of transience. Like you, these people are often on the move, disappearing from your station but reappearing in far-flung hubs hours later.

That said, they’re not all so compelling to me. Many of your shipmates seem to suffer a dose of the “niceys”. Conflict is resolved readily, and kindness prevails more often than conflict erupts. The drama you might expect from a crew of misfits forced into proximity on a starship is set aside for a quieter, familial bonding that sometimes makes me smile sweetly, and sometimes makes me yawn and wish for an abrasive bastard to show up. For many others, a kinder-hearted crew may be a winner. But I know I’m not alone in yearning for a scumbag or two in my fictional ensemble.

Take your saviour Serafin, for example. He’s a good-hearted and competent pilot, and your close buddy throughout the game. I would like a friend like him in real life. In-game, I wanted to hiss him out the airlock. As your first companion he fulfills the role of a Mass Effect starter companion – someone who will explain things to you and voice vanilla misgivings. He is strong-willed, caring, thoughtful, and resolute. I wanted to abandon him in an asteroid field after a couple of hours.

Instead, Serafin accompanies you along a main quest that never quite interested me as much as the various side gigs. I found his narrative hand-holding irritating even – frequently taking you aside to tell you which spacerock will be the next best hub to visit. It’s nothing a Bethesda main quest character doesn’t do, but after the relative looseness of Erlin’s Eye, where I really did feel in control of my wanderings, there is sometimes a feeling here of being shuttled from plot point to plot point, rather than meandering through the world at your own pace, picking up the stories you want and dropping others at will.

In fairness, some of the shuttlestops are fine adventures. You may help a union organise an interstellar strike, or delve back into the shadowy streets of the Darkside (scumbag territory that belongs to Laine). But I was anticipating a more open-ended tale right from the beginning. By the time this freedom is afforded to you as a player, you’ve basically seen the whole system and met everyone of note. It is geographically a broader game than the first, yet it feels somehow more confined.

Don’t let me scare you too much. Scenes are still well-written, the expressive prose maintaining a good eye for body language and mannerisms. An engineer will wipe their hands on rags as they speak to you, hacker kids will betray their mysterious ulterior motives with steely looks. It has all the panache of well-crafted genre fiction, yet doesn’t overload you with paragraphs of lore, keeping to the cadence of good interactive fiction. At least, this is the case for much of the game. Later sequences can get bogged down in long descriptions of abstract hacking or space architecture, the game sometimes forgetting to check its own wordy enthusiasm.

Thematically, it’s loyal to its progenitor. The first Citizen Sleeper hauled its disdain for interstellar capitalism right to the centre of your story. You were a gig economy robot with a terrible addiction to a repair drug; a walking iPhone that grew a heart and ran away from the Apple store. Starward Vector doesn’t deviate from those themes of coercion under capital, except to sometimes explore the fate of refugees fleeing war. It also revisits the dysmorphia that results in having a body that doesn’t feel truly yours, and the relief that might come from realising you are not alone in such a struggle.

In all this, it again treads a line between thoughtful speculative fiction and popcorn sci-fi the likes of Space Sweepers. I liked befriending a stray cat in zero gravity to summon the memory of my previous bio-self in a poetic passage about identity and comfort. But I also enjoyed meeting an ancient drilling worm in the belly of a cursed asteroid, still digging after thousands of years like some robot Shai-Hulud coached by the Energizer bunny.

It often loses itself in the long spool of its main quest, in the runaway passages that could have been shorter, and in the stories of characters who sometimes feel like they’re hijacking your tale, turning it into a choose-their-own-adventure. But Citizen Sleeper 2 still manages to deliver some heartfelt moments in a sci-fi world that feels more colourful than the likes of Starfield (again), despite being the work of a much smaller team over far less time. It’s finely made sci-fi, even if I still prefer the noodles on Erlin’s Eye.

Disclosure: Jump Over The Age’s developer Gareth Damian Martin has written for RPS

Add comment