“When I was young,” the villager washing garments in the river says, “I thought it was enough to clean the dirty laundry once and be calm. Not that it will get dirty forever.” I’m not sure I’ve ever felt the crushing weight of universal entropic decay so keenly as in that RPG maker textbox, nested upon Felvidek’s nicotine-stain hues. I’ll need to clean my keyboard soon. I keep taking screenshots of Felvidek. I can’t take enough. I want to make a scrapbook of every character and every line. Neither my laundry nor keyboard will ever be clean forever either, but if I hate Felvidek for emphasising that, I love it for reminding me that all the best art is buttressed by an irremovable layer of deep, thick grime.

Felvidek, set in 15th century Slovakia, is all about honeyed words and grubby deeds. Pavol is an alcoholic knight with marriage woes. Matej is a seemingly devout though often hilariously flexible priest. They’re a farcical if committed double-act who often alternate between curbing and encouraging each other’s worst instincts. Jozef, a local lord that constantly pesters everyone in earshot to play board games he’s imported from yonder lands, sends them both off to investigate some strangeness at a fort. Cue a tale of secret cults and cursed beans, dysentery and infidelity, and the importance of always rocking a shit-eating grin, even when you’ve just been shanked in the belly by a loved one.

It’s a small map and the game is short, although I don’t think it needed to be any longer. You sprint about on its overworld, explore, talk to folks. Travel doesn’t take long, so I keep going back to the village to hear the woman washing garments in the river talk about the clothes that get dirty forever. About decay. The guitar tones that score this village are alcohol-wipe clean, but every so often a cataclysmic screech of static bursts out from somewhere deep underneath and engulfs them. Everything we think is stable is piled on top of chaos like sandcastles on fault lines. Everything we clean will get dusted in dead skin again soon enough. Every time you return to Jozef, he helpfully reminds you where to go next. Structure. Chaos. Structure.

There is a chaos buried under the villages and castles of Felvidek, and you will have to unearth and stab it later. But your first scrap will likely be the castle armourer, who keeps telling Pavol he stinks like a polecat until you’re forced to beat him into selling you gear. And it’s gear you’ll want, as it’s the only way to get stronger. The game describes itself as a JRPG, so fights against such polecat-prejudiced armourers are turn-based and stuffed with status effects. There are no character levels, but consequently, no force-fed fights or random encounters: violence feels scripted in the theatrical sense, where it’s story beat-downs only.

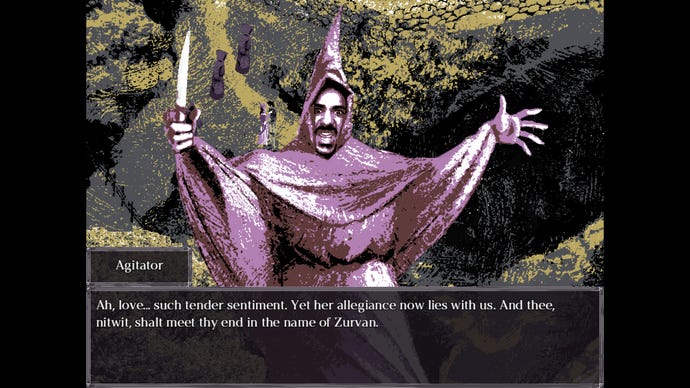

Fights also feel deadly, even if you’ve got an inventory stuffed with heals and are never more than two scraps and a short sprint away from a full party heal at a church. But why pray to an absent god when you could instead watch Pavol guzzle a bucket of sour cream in first person mid-battle? Why shamefully prostrate yourself in penance, when you could watch a drunk, bleeding knight rapidly spoon porridge into his face so he has enough ability points to mace-pulp a purple-gowned cultist?

It lends the game a terse tone theatrically, baroque in the moment but skimmed of fat as a whole. As does the prose, written with the sort of knowingly modern send-up of plummy medieval flourishes that means every line takes twice as long to read as it looks, but is very much worth the extra effort. Sometimes the writing is witty and crass and crested with pathos, and sometimes it’s just funny because of how convoluted it is. Reading it is like chewing massive mouthfuls of good bread: takes some jawing, but worth it to watch Pavol and Matej discuss the theological nuances of a clergyman visiting a brothel. Some of it might be period accurate, but sometimes it’s a guard who you gave an almost correct password to saying “thou knowest what? Come hither.” It’s a little bit Shakespeare, some Stoppard, Cervantes. And yes, a bit Python.

I gather you can finish Felvidek in about two hours, but it took me about double that. Bizarre and loathsome individuals have coin, if you feel like being a knight while you’re waiting for the tavern to start serving again. A stray conversation with an NPC gathering pears for brandy takes on all the twisting depth and presence of a lysergic parable, and a choice as simple as to whether to steal a sip of that brandy might see Pavol awakening in darkness to a place of mutants, static wails, and deep confusion. The story takes place in phases, locking out some quests and offering new ones at certain moments. Mostly, you’re free to explore, but sometimes you’re locked in for a while, like when Pavol, hardy nutter that he is, is still afraid to go back into his master’s castle in his underwear after having his clothes stolen.

I wanted to make Pavol my own a little more than the game let me. He’s an alcoholic in prose, but rarely ever in deed. Different types of collectable spirits are plentiful, and I think I expected him to get the shakes after a while, performing worse in combat if I didn’t keep him topped up, but no such fun. The grime and the death and the RPG combat, and especially an early encounter that killed me right at the beginning, put me in mind of the Fear and Hunger games. I think Felvidek would have benefitted from a bit more of this deadly choose-your-own-demise sadism, but on reflection, only on the replay. What you get instead is a perfectly formed and paced single viewing, told by a black humoured, bawdy bard who weeps in secret at night over the inevitable decay of everything, but never drops the shit-eating grin for a second.

This review is based on a review build of the game provided by the developer.

Add comment