Harold Halibut has the vibes of a game that should be 4-6 hours long and is, inexplicably, 10-12. It’s inexplicable not only because it’s a slow game low on interaction – the game is really just a plot delivery mechanism; a TV show you can walk around where you advance the story by pressing A – but also because it’s a game created using handmade miniatures. It’s a sci-fi animated dolls house under the sea, self described as “a cross between a game and a stop motion film”, and if my game required that amount of labour I’d edit that script down. Then again, there aren’t that many locations, so maybe you’d really want to show them off.

I love miniatures, and Harold Halibut is beautiful. It’s also a lovely story about finding yourself and your place in the world, even if that place is unexpected, and having the courage to take that step. There are unexpected silly bits and strange bits and bits where people break into song, and bits where you read undelivered letters. But, at the same time, I totally understand why some people would find it boring.

You play the titular Harold. He’s the odd-jobsman on the Fedora, a former colony ship that left a seemingly doomed Earth and crashed on an ocean planet. The inhabitants disassembled the Fedora and made it into a sort of cute Rapture-from-BioShock – there are different districts for work, play, science, etc., and you get around through a network of tubes. The details are sometimes unbelievably great, both specific and odd, and the way some sequences are filmed are downright cinematic in a way that many game directors think they are, but are not really.

The Fedora’s vibe is sort of 70s sci-fi with bright colours, and all a bit janky and jerry-rigged together. Whenever you enter or leave a district you get spritzed with disinfenctant from an old school metal shower head. There’s more to look at than, by rights, there should be. I sat in the tiny lounge in the lab area, where Harold lives, and watched some in-universe ads, one of which was for the ski good shop (the existence of the ski shop is both very funny and also pivotal to the story in a way I will not explain).

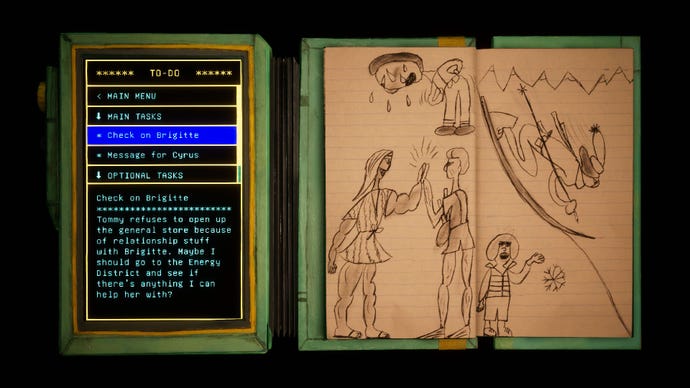

Harold has a kind of PDA that gives him a to do list, and where he can receive messages from other characters (the game sometimes skips a few weeks, and you’ll have loads of new messages when that happens. They’re cute!). He also has a notepad where he draws stuff that happens to him – it’s later suggested he’s dyslexic, or something like it. The drawings are another way you can get glimpses of what Harold really thinks about the world, when he doesn’t always express it otherwise.Image credit: Rock Paper Shotgun/Slow Bros.

The plot is driven by a few things. Firstly, the Fedora is facing an energy crisis, and has been for a while, which isn’t great when you live underwater. At the same time, a once-in-a-lifetime window to take off from the planet without getting hit by a solar flare is coming up. On a third hand the All Water Company (a business that became the de facto government of the Fedora) appears to be keeping secrets and is in conflict with a clandestine rebel group. And, finally, Harold finds an aquatic local knocking about in one of the filtration systems. Hazza ends up at the forefront of most of this because he’s the lab assistant for the chief scientist Jeanne Mareaux, though he’s passive enough that everyone else just asks him to do stuff too. And he does it!

Katharine found this frustrating in her preview, but I really liked Harold being pranked by some of his coworkers. Harold Halibut isn’t an RPG, you don’t get to be the Harold you’d like to see in the world. You’re a passenger on Harold’s journey here, and it’s heartwarming and quietly triumphant to see Harold’s worth gradually recognised by both the people around him and Harold himself, as he helps so many people around the Fedora in different ways – as well as making new, close and emotionally resonant relationships. Harold starts to express annoyance at how his ex talks to him, and gives advice to others rather than agreeing with them. Eventually he feels confident enough to make a big choice about his life, even shouting at Mareaux to be heard when before he let her speak over and ignore him.

The characters are odd, from the school teacher who wears a silk robe the whole time, the general store owner with a secret identity, and the group of identical sibling All Water employees who are concerned by the black sheep of the family (he wants to sell hot dogs). But although the specifics of their problems are unlike normal ones, they’re recognisable in their basics: family, love, loss, anxiety, wanting to belong.

But Harold Halibut doesn’t shy away from being weird. At one point early on, Harold bursts into a musical number about wanting more from life, one of a few surreal sequences that bend reality on the Fedora. There are montages that sort of recall Rocky or Scarface but of Harold doing wholesome things and getting to know people. He joins the unlikely revolutionaries to spy on the head of All Water and tries to infiltrate her office as a cover of Bella Ciao plays; he tries a tiny artificial ski slope; there’s an achievement for watching a mime perform a weird one-man show. While most of the game takes place on the Fedora, Harold also goes to another community which is full of strange little interactions and is an organic, colourful place that’s the complete opposite of the Fedora. It’s funny, charming, and crafted with great attention to detail in the sets and the writing.

At the same time, Harold Halibut is very slow. You’ll mostly be talking to people and then, at their behest, heading off to talk to someone else, and you will become intimately familiar with the various stairs and corridors and Harold’s odd little run. There aren’t any puzzles, it’s just conversations and being curious, and 10 hours of it do start to feel like a long time. No one would allow Wes Anderson to make a 10-hour film for exactly this reason. I think you could snip a decent chunk out of Harold Halibut, especially the early chapters, and come out with something leaner without it being meaner. But even as it is, the ending is a good payoff to a sweet story, with plenty of chuckles and surprises along the way.

This review is based on a retail copy of the game provided by the developer.

Add comment