Every fascist in this game has a cold. The Hitlerites and blackshirts of Indiana Jones And The Great Circle sneeze and cough as they patrol the dig sites of Gizeh, or the marble corridors of the Vatican. Although this is the Machine Games’ clever way of letting you know where your enemies are at all times, it is also mildly funny, as if all the Nazis have been secretly kissing each other, spreading the same rhinovirus from Italy to Egypt to Nepal and beyond. More than that, it’s a stubborn reminder that, despite the many hours of perfectly motion-captured cinematics that accompany all this, you are still playing a video game. A snotty tissue that separates the Indy of taut two-hour cinema and the Indy of a sweeping first-person punch ’em up that will take days to complete. All this is to say, you will notice the difference. But that might not matter; they’re both still Indiana Jones.

As is Disney’s wont, the outing is militantly on-brand. The opening recreates Raiders Of The Lost Ark’s boulder-escaping intro sequence with a beat-for-beat loyalty that borders on obsessive. Although it deviates from the movie in one important way: it lets you investigate whether the first waterfall you see has a cave behind it – a good joke, and the first clue we’re playing a game and not just rewatching a scene we may have witnessed countless times.

It’s thankfully not long until you’re out of this famous scene, and exploring the artifact collections at Indy’s university campus. There’s a break-in, and a mummified cat is stolen straight from its display case, which sends Indy on a round-the-world adventure to find out why this one dead moggy is so important. Also, a mysterious giant knocked the adventurer’s lights out in the process of burglarising said ex-feline, so we must uncover who that guy is too. Soon enough you’re stealthing past guards, solving archaic puzzles, opening hidden safes, getting into knuckle-bruising scrapes, and donning disguises to blend in with the locals.

But I like how Machine Games begin our boy’s journey in the exact space he’s always harping on about – a quiet museum. And the many props that fill its glass cases are representative of the visual attention to detail that will follow for the entirety of his globe-trotting trip. This is a lavish blockbuster with no expense spared on the environment art and set dressing (and no PC spared either). The amount of props alone – many recreated from actual historical artifacts or real world artworks – is intimidatingly impressive. There are more pots in these tombs than a Dark Souls player could feasibly roll over.

That attention also shows in the stray conversations between NPCs in the street, in the heavy snow that leaves a soft trail as your companion wades through it, and in the animated cats that lounge around waiting to be photographed for stray “exploration points” (these will help unlock skills – more on those in a bit). I know “graphix is gud” is to be expected in a multi-million-dollar Bethesda blowout, but it does feel important that a game set around an enduring relic of Hollywood should simply look bloody good. The lighting, in particular, channels the beams and glows of cinema, and likes to lie in familiar dramatic lines across Indiana’s face as he looks up in awe at a statue or hides behind a box from Mussolini.

As both an Indiana Joneser and a fan of guns-down exploration, it also feels purpose-built to make me happy. I often want my first-person shooters to slow down and make good use of their space, to make it explorable and intricate, and to pace out their action with lots of quieter nosying about. Indy’s Big Round Ring satisfies that desire for a wandering playspace. Its levels are grand and open. The Vatican is full of gates and walkways that will bring you back to the place you started with satisfying shortcuts. The sandy dig sites around Egypt’s pyramids contain so many tombs and secrets I had to force myself to focus on the main story just to try and get this review done in time (I failed – this review is late).

It helps that much of it is set in locales where you might yearn to be a tourist in real life. You can fast travel using signposts found throughout the levels – but why would you when learning the layout and going off the most weathered paths make wandering from place to place so gratifying? That exploration gets rewarded not just with the usual collectibles but also with skill books that upgrade Indy in some classic gamey ways. For me, conflict was usually solved by battering backturned fascists with a single good donk on the head with a hammer – a stealthy approach. But some books toughen your fists, increase your stamina bar, or upgrade your whip to let you yank even the biggest, bruisiest enemies toward you. All useful when the fighting breaks out in earnest.

For me, this meant completely ignoring the revolver you always have to hand for emergencies. Instead I relied on the many melee weapons that are scattered in almost every room and desert tent. Crutches, brooms, shovels, whiskey bottles, mallets, rakes, bronze busts of old Popes… weapons are everywhere, it always feels like something useful is within reach, and some skullcrackers are more durable than others. A wine bottle will only do you one desperate smash (they can also be thrown to create a distraction) but a wrench might last five or six solid thwacks. One skill book lets you do more damage with the final smash of a melee weapon – the last donk before a mop splinters or an upturned rifle clatters to bits.

All this adds to the combat’s general sense of weight. you have to punch with left and right triggers on controller, and parry with light taps of the left bumper at precise moments. Melee fisticuffs in first-person has always been a hard thing for action games to pull off, and here too it can get overwhelming. Crowding the player is a hard problem to solve without resorting to obvious enemy turn-taking and Ubi-like warning indicators (a combative crutch Machine Games seem to want to avoid). Here you are a punchbag under pressure, with limited stamina and slow-to-recover biffs that suggest the correct way to play is to not get into open fights at all. Or if you do, to try and make sure you’re only ever fighting one or two people at a time.

All this meant I didn’t find the punching all that enjoyable at first. Yet once I fiddled with combat difficulty options to make things more forgiving (you can set the block to auto-parry incoming hits) I started to enjoy it not as a challenging encounter to overcome but as a mostly risk-free action sequence, dancing around my opponents and admiring the animations, as when Indy shakes off a final painful knucklewhack. Playing this game in “tired parent” mode is viable.

That sense of heft is not just in the fighting though. Carrying bodies to chuck them in a hiding place also drains your stamina bars very quickly. Levers and locks and all sorts of outlandish historical devices need to be yanked or twisted with an extra flick of the controller’s stick, or tap of the whipyank, to get their animation to complete. There are a hell of a lot of satisfying “kerclunk” noises in these catacombs and corridors.

In fact, the sound design in general is very solid. Aside from all the signalling sneezes and conspicuous whistling necessary to keep you alert to all the fash you can bash, Indy’s whip has the crack of a high caliber sniper rifle. And the soundtrack is, once again, chest-pumpingly loyal in its toots and honks. Action sequences get all the triumphant trumpeting you expect, while sneaky moments see Indy accompanied by his coterie of coy flutes and plucked strings tip toeing along with him through the stealth sections. When you smash people on the noggin in surprise the tension is dissipated by a dramatic “wwwWAH!” that you may unconsciously recognise as just one of the game’s many John Williamsisms.

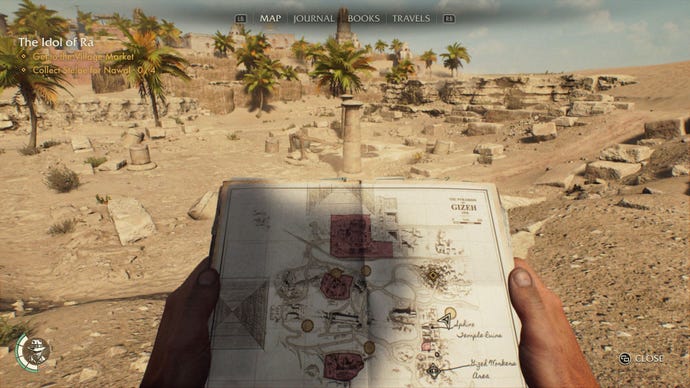

As a work of adaptation, much of this stuff is to be expected. And it’s interesting to see how Machine Games have handled the most video gamey elements. How do you make recovering health feel like Indiana Jones? You let him scoff biscotti and other local foods (technically this gives you “buffer” health, but it still counts). How do you make a “last stand” self-revival skill feel like Indiana Jones? You make the downed player crawl towards his hat and put it back on. How do you make a map screen feel like Indiana Jones? You let him hold the actual map and look down at it even as the player walks around.

None of these are super innovative, but I’m always very happy to see a Far Cry 2 style map in games where it feels right. And it is proof that Machine Games have gone about each system in a thoughtful way. In the same way Creative Assembly finally translated Alien into the medium of games with Alien: Isolation, I feel like this finally understands some of what makes Indiana Jones appealing: solving an ancient riddle by examining old notes in your journal, fumbling for a nearby weapon during a scrap only to grab a fly swatter, cosplaying as a member of the Wehrmacht and throwing a stick of dynamite when your identity is revealed.

In these moments it’s also notable Indiana Jones And The Large Hoop doesn’t offer any classic stealth game means of losing your pursuers in the event of being spotted – no lockers or hay bales here. If you’re sighted, it’s basically time for a big brawl. At first, I found that a little frustrating, I instinctively wanted to save scum. But after embracing the biffing I have realised this too feels truer to the character of the films. Indiana Jones doesn’t hide once he’s caught. He gets into a stupid fight.

Troy Baker has said that Bethesda didn’t ask for a “bang-on impression” of Harrison Ford, but he nonetheless delivers a quietly convincing version of Ford’s adventurer, with all his finger wags and wry side-of-the-mouth smiles. It is a reproduction of Ford’s younger face we’re looking at the whole time, and there are uncanny valley moments in looking at Dr Jones when you feel “this isn’t exactly right”. But the other performances quickly take the heat off (Voss, your principal Nazi antagonist, is particularly fun to dislike). You forget all about Baker.

In the same way, Machine Games have reproduced the experience of the Lucasfilm movies in a 99% accurate form. And they have done so in a manner only a megafunded Bethesda studio with a lot of Nazi-killing experience could. Yes, the video gamey seams stand out as you scarf down croissants for health and hear another bigot coughing behind a wall. But just as I’m not interested in Baker’s performance reaching some unobtainable ledge of authenticity, I also don’t want my adventure to abandon the language of games where it doesn’t make sense to do so. I’m happy for this to be exactly the kind of expensive, cinematic, blockbuster explorathon it seemed predestined to be. Sneeze away, little Nazi. I know where you are.

Add comment