Mechanically, Life Eater uses a diary-based puzzle system in some really interesting ways, but it struggles to say anything meaningful about the shock-factor setting it’s gone for.

Few game ideas will turn your head quicker than one about abducting people and murdering them. It’s an idea that courts controversy for the shock factor that comes with it, in order to stand out, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing if handled right. I don’t mind it here because Life Eater is a genuinely interesting indie game and not a tasteless cash-grab. Nonetheless, it’s still an uncomfortable premise and an uncomfortable game – uncomfortable in some interesting ways but uncomfortable all the same. But I feel like if you’re going to go there, you’d better have some interesting things to say when you do, and ultimately, I don’t think Life Eater does. To me, it feels a bit frightened of the controversy it courts. But let’s come back to that because there’s a lot of good stuff in between that I want to talk about first.

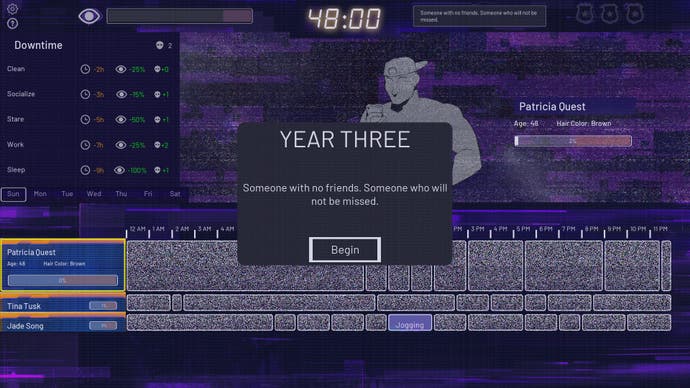

In essence, Life Eater is a puzzle game – it’s not the gory action murder simulator you might be fearing. Far from it: the moment-to-moment gameplay actually revolves around staring at people’s day-to-day calendars, a kind of diary of events, and gradually filling them out. You do this by clicking on an empty space and selecting one of a few stalkery things to do to reveal them, such as carrying out a DDoS attack or hacking their phone, or peering inside their window. Activities range from subtle to brazen, and what you can do depends on a couple of things.

Time and suspicion rule everything. Every action costs time – think of it as a currency – and every action raises suspicion, and managing either badly can mean a game over. You have an overall time limit for a mission, so every action whittles that down, and you have a suspicion gauge that, if filled, calls the authorities on you, which as a serial killer, you obviously don’t want. What you opt to do depends on all of these things working in tandem: do you go big or small, loud or quiet – how much time and suspicion can you spare? One more thing: you can lower suspicion with downtime activities like “staring”, which cracks me up, but again, this is all done at the expense of time.

As you fill out the diary, a completion gauge fills up, and when it reaches a threshold point, you’ll be able to abduct someone. Do this and you’ll move to part two of the puzzle: a memory test – a rather gory memory test. You’ll see the inside of someone’s torso, so their lungs and intestines and all that juicy stuff, and then you’ll face some questions about that person’s life. Does the person you were just stalking have children? If you think they do then please remove some of their ribs. Does the person you were stalking live alone? If you think they do then please whip out their intestines, and so on and so on until you’re confident you’ve answered all questions correctly and can complete the ritual successfully, thrusting a stake into their heart. None of this is particularly gory by the way – it’s more cartoony – but it’s still uncomfortable given the surrounding circumstances of the mission and game.

In terms of what you do in the game, though, that’s it – those are the mechanics. What’s clever about Life Eater is how it uses that simple base to build quite complex and thought-provoking puzzles. Much of the flow of the game is about gradual discovery – how to use mechanics, where to look for clues – and it doesn’t take long for the difficulty to increase. The first mission I breezed through but the second mission I had to redo a few times, and redoing missions is fairly typical in your overall progress, because failing forces you to look more closely and wonder why.

How are you supposed to know if they live alone, for example? The game never explicitly tells you, nor does it tell you if the people you’re following have any children. To discover the answers, you have to dig around a bit and – and this is the bit I really like – use actual logic to find the answer. Which daily activity do you think would be most telling when considering whether someone lives alone, for example? And what would a parent be most likely to do? That’s the kind of thought process that bubbles up playing the game. It’s no exaggeration to say you’ll feel a bit like a stalker, which is an unusual and, well, memorable feeling to experience.

When you’ve understood one layer of the game, Life Eater then presents you with another. You did quite well abducting a single person, the game will say, so how about now abducting two? Or, how about investigating someone’s life indirectly, by examining the lives of people around them? To do that, you’ll need to explore multiple timelines at the same time, looking for corroborating – or revealingly conflicting – evidence. Sometimes even the mission briefs are puzzles, such as “find a monster” – how are you supposed to know which one of the people before you is that? Whatever the twist, the game consistently finds a way to up the challenge and intrigue each level, and there’s a thrill born from this in seeing what’s next.

Well, I say “thrill”, but you never quite escape the uncomfortable truth of what you’re doing it all in service of: abduction and murder. It’s something fundamental you can’t help but be affected by. You are snooping into someone’s life in order to steal them and then kill them. Worse, you are learning about them before you do it, calculating sometimes, based on the evidence of their lives, who should live and who should die. You see their private lives and judge them for it, separating loved ones, cutting short the lives of young ones, and it’s – I’ve said it before – uncomfortable. Though, there is undeniably a thrill that comes from it, from living the kind of taboo stalker fantasy that TV series like You relish in – this is far from the first time someone has done it. It’s a very effective idea.

But was the idea here ever anything more than to provide an arresting backdrop for a game? Because to come back to my original point, the game doesn’t quite fulfil what it sets up – it doesn’t stick the landing. There’s a story running through the game, you see, that plays out in between missions in a series of suitably ragged slides with voice over (one of the characters is voiced by the game’s creator, Xalavier Nelson Jr) that remind me a bit of Hotline Miami, and the kind of edginess on display there. It’s here you learn more about what’s going on and about who you – this mysterious murderer – are, and who the god is you apparently serve.

As the game builds, so too do the questions surrounding you and the expectation of the answers that await. What, you will wonder, does it all mean, and why are you doing these things? What are the consequences of your actions? But the game never really answers you. At the climax, it’s like a door opens and all that pent-up mystery just floats away. And regardless of your choice at the end, all you get is a short outro that manages to avoid giving any answers and leaves it all up to you. ‘Oh, is that it?’ I remember thinking. It’s a shame.

Perhaps it’s understandable because to be another way, the game would have to wade head-on into some pretty heady topics and have capital-O opinions about them – about things like mental illness, and abduction and murder, and there’s no easy-reading there. Perhaps it’s better not to half-arse it. But it feels like a cop-out to me and as though the game flirted with an idea it didn’t have the stomach to see through. Or perhaps more accurately: that the game found a cool concept that turned heads but struggled to wrap a story around it. Had Life Eater found a way to bring it all together, it could have been something startling. As it is, it’s a few hours of engrossing puzzling in a unique setting (there is an Endless mode listed on the main menu, but it’s “coming soon”) but little more.

A copy of Life Eater was provided for review by Strange Scaffold.

Add comment