In the latest Minecraft Live, developers Mojang revealed a “Vibrant Visual” overhaul for a game that is now older than many (most?) of the people playing it. Initially planned for the game’s Bedrock edition, with a Java version update to follow, it garnishes Minecraft‘s blocky wilderness with directional lighting, volumetric fog and other gimcrackery you might recognise from more recently published open worlders.

Back when I was a mod-phobic Vanilla player, I would have sneered at all this. Minecraft is not supposed to have “subsurface scattering”, whatever that means to regular mortals. It is not supposed to look high fidelity, or high tech. It is supposed to look like, well, Minecraft. These days, my reaction is less outrage and more curiosity, mingled with vertigo at the entangling of these trendy flourishes with the pixelgrain of what is still, on some level, Infiniminer touching grass. Whatever you think of these Vibrant Visuals, it’s interesting to follow Mojang’s efforts to tinker with and flesh out an aesthetic that was arguably ‘perfected’ in 2009. It’s also interesting to think about what “vibrant” might look like, 16 years from now.

.png?width=690&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

I’m always tempted to call Minecraft’s aesthetic “timeless”, which is objectionable for a bunch of reasons. It risks brushing aside how the developers have tinkered with that aesthetic since the first public alphas – devs like Mojang’s lead artist Jasper Boerstra, who joined the crew in 2017 and was promptly asked to redraw every last block texture while introducing himself to the fans.

In general, “timeless” is an utterly vacuous descriptor. No artwork and no visual aesthetic has some kind of essential baked-in magic that ensures it will always find a following. Contexts alter and expectations change. People die and other people are born. Artworks find attention and lose it and find it again. Still, if it’s silly to suggest that certain aesthetics simply have more staying power, I wonder if there’s something constructive about aiming to be “timeless”, inasmuch as it’s another way of framing the issue of video game preservation. Cultivating timelessness is a form of speculative, gently anti-capitalist fiction: what will different individuals, groups and generations consider “vibrant”, a few decades from now? What will they hold onto, amid efforts to repeatedly sell them all-new, soon-obsolete “vibrancies”?

I wonder if Minecraft’s long-departed and disgraced creator Markus “Notch” Persson asked himself that question, back in the noughties. I’ve never met Persson, but I’ve spoken to a lot of the people who worked with him back then, and his original approach to texture creation seems fruitfully open-ended.

Minecraft is a proud example of what Mojang creative director Markus ‘Junkboy’ Toivonen once appreciatively described to me as “brute-forcing” art production. The original block textures are based upon minimal formal training in the visual arts. To fashion them, Notch created a bunch of tiny 8-by-8 or 16-by-16 pixel squares and futzed around with the mouse until he had something resembling soil, stone and treebark. The limited canvas size helped in that it makes a virtue of approximation and abstraction.

Combine that deceptively artless texturing with layered, procedurally generated landscapes, introduce a rainbow of “cloth” block types for the fancier builders, and you have a mix of pastoral LEGO sandbox and 3D pixelart editor that lent itself well to the emerging Youtube Let’s Play scene. The other advantage of this ‘programmer art’ is that it’s easy to copy and replicate, tempting to improve upon: just load up the textures in Microsoft Paint, and jimmy those pixels as you please. If this was a strategy on Notch’s part, it has paid off amply: there’s now a whole industry of people who specialise in making Minecraft look like everything from an unholy X-ray dimension to the European Middle Ages. Mojang’s efforts to make Minecraft more vibrant are just one strand of this community-wide experiment with Minecraft aesthetics.

Ironically enough, the developers who are currently thinking hardest about how their aesthetics might endure are probably the creators of live service productions, with business models that require a certain lifespan. These are projects that aim to become “platforms” while also committing to the precarity of an online requirement (and the crushing ambitions of executives who dream of making the next Fortnite) – however endless their roadmaps, they are Faustian bargains and sandcastles in the sea.

Still, I can think of at least one non-live-service project that is deliberately angling for Minecraft-style longevity in terms of its art direction, albeit in a very different way: Billy Basso’s superb creature feature Animal Well. As I wrote for the Guardian in 2022, Basso conceived of Animal Well as a “time capsule”, designed to be playable and worth playing for a decade or more. The game avoids some of the features that make preservation more difficult: it doesn’t have online requirements, and there’s no DLC or update strategy, though Basso has inevitably had to patch a few bugs after launch. The game file is absurdly compact at less than 50MB – you could send it as an email attachment. It also contains software libraries that other games would expect to find installed on your computer, making it more independent of operating system changes.

It’s not just about ‘future-proofing’ the code, however. Basso’s time capsule parallel also extends to the design and aesthetics of Animal Well. The game’s most elusive puzzles were designed to take years to solve, and this opaqueness of design suits the emphasis on preservation, because a game that keeps its secrets is one players will keep returning to. This idea feeds through into the pixelart and its symbolist or archetypal vocabulary of tools and objects. Discussing the usage of rotary-style telephones as save points in Animal Well, Basso told me that he wanted “to make something that feels timeless, in a sense, but also anachronistic” – a landscape of objects that are both peculiar in the context and “immortal”, in the same way that anvils remain a familiar trope in North American cartoons.

I enjoy the echoing ambiguity here: Basso wants the phones to feel like they belong to a certain era, but also like they transcend chronology. It’s the irreducible contrast between those things, you could say, that makes Animal Well “immortal”, in that the disconnect sharpens the suspicion that this chasm of creatures still harbours a few more discoveries.

Basso’s project is a template for what I will presumptuously call a more “constructive” approach to video game preservation, which treats longevity as a positive and holistic artistic principle, informing the entirety of a game’s concept and execution. I’d love developers to think and talk more about how a game might become “timeless” – not just in terms of “purely” practical or external problems like operating system compatibility, but in terms of, say, the textures and choice of objects and how these things might kindle a player’s curiosity, even if you strip away all contemporary context. Again, while “timelessness” is a vacuous ideal, designing for it can be a useful social project. It might help the culture of game preservation seem less sorrowful and nostalgia-driven – less about rescuing old games, and more about nurturing the conviction that good art should last.

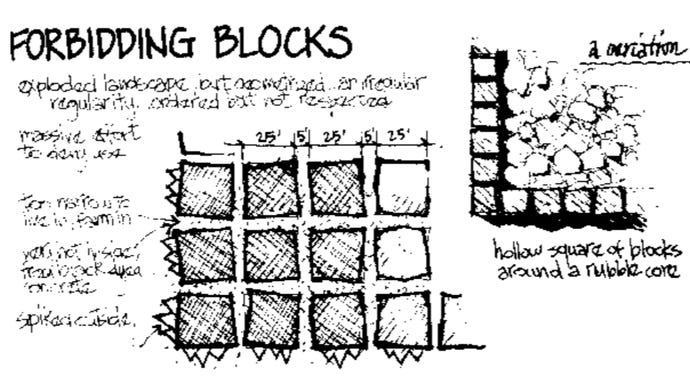

This is an absolutely terrible closing parallel, given the above emphasis on positivity, but perhaps Minecraft’s next visual update should take inspiration from another, less romantic kind of time-capsuling: long-term nuclear waste storage. Back in 1992, the US Sandia National Laboratories commissioned a panel of experts to design a 10,000-year marking system for radioactive burial sites – places of “vibrancy” in the sense of vibrating with energy. The Sandia panel published a report detailing some possible hostile architectures they felt might deter unsuspecting visitors from future cultures: “immense lightning-shaped earthworks radiating out of an open-centered keep”, and fields of “wounding forms, like thorns and spikes, even lightning”.

In the context of Minecraft, my eye is caught by the Forbidding Blocks, a maze of “deliberately irregular and distorted cubes”, each roughly 25 feet a side, which form streets that “lead nowhere, and… are too narrow to live in, farm in, or even meet in.” The writers summarise it beautifully as “a massive effort to deny use”, but inevitably, these descriptions and the accompanying illustrations are as enticing as they are disturbing. They look like something you’d find on Minecraft’s infamous 2b2t server. They absolutely look like somewhere you’d expect to find treasure, regardless of the era. Game developers might take inspiration from that feeling of troubled enticement. Is it helpful to consider what mixed emotions your creation might evoke, a hundred centuries from now?

Before joining RPS, our news editor Edwin Evans-Thirlwell wrote a book about Minecraft’s history in collaboration with Mojang and Microsoft. He’s not receiving any royalties or similar on-going payments.

Source link

Add comment