Nomada Studio follows up on the striking Gris with an effort that’s poignant and precise, if maybe just a tad melodramatic.

Forgive me reader, but I’m going to reference a tweet. The other day I saw someone I don’t know talking about films, and it said: “There is a loss in going from Cronenberg, who is obsessively steeped in Heidegger, McLuhan & Freud, to his legions of imitators, who are obsessively steeped in Cronenberg, giallo & The Shining.” They may or may not have been right (reading between the lines, they were probably talking about The Substance, which is a film I haven’t seen yet – and hear is very good! – but which is kind of beside the point anyway).

But it’s an interesting thought at least: what counts as legitimate influence? Where’s the line between being inspired by something and just plain aping it? And what happens, over time, when all your inspirations solely come from your own contemporaries in the medium – their own style, their own decisions – rather than from your own original source, whatever that might be? And then what happens when you repeat that over years or even decades, creating a series of faintly varying facsimiles, each new thing referencing other things before it that, way back when, had original, organic influences we’ve long since forgotten?

Aside from reflecting on just how my social media feed got so pretentious, it also got me thinking about video games, which are if nothing else extraordinarily self-referential (in Roguelikes and Metroidvanias – never mind the Doom Clones of old or Soulslikes today – we even have genres named after games themselves). It’s probably a little bit unfair to bring it up right now, in the case of Neva, a game that is utterly, wildly beautiful, elegantly designed and, in one brief sequence in particular, bordering on just a little bit genius. There is also inspiration here from the real world, so let’s park that whole Cronenberg thing for a bit and come back to it.

For Neva that inspiration is parenthood, which admittedly has become a very common inspiration for video games, from 2018’s God of War and beyond. But more specifically, and more interestingly, it’s the cycle of parenthood as life moves on. The progression from cared-for child, to nurturing parent, and then an adult who must care for parents of their own in later life and, eventually, be cared for again themselves.

“I find myself between two generations,” creative director Conrad Roset said, talking to Eurogamer’s Victoria Kennedy about how his own experiences have become his influence. “I have my children, and I have my parents. And now, I am taking care of my parents, who once took care of me in the past.” Lead producer Roger Mendoza, also a parent, said the same: “The idea was to make a game where you could translate those feelings of raising someone… That’s why it was important for us to have a companion. So you could have this full cycle of ‘you start taking care of someone, you grow up with them, and then they end up taking care of you’.”

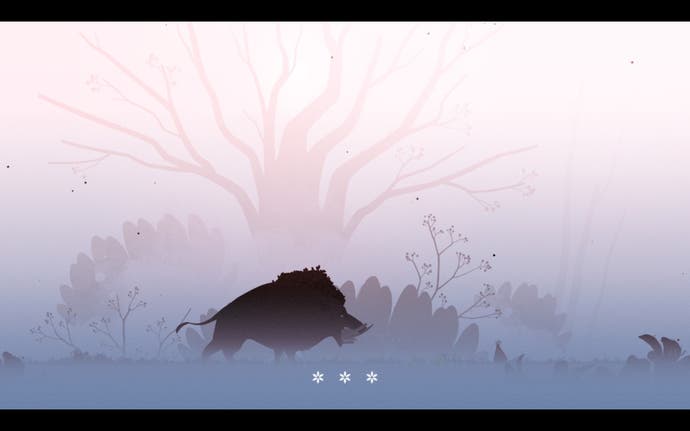

In Neva this is borne out through a sequence of seasons – summer, autumn, winter, and spring – as you, in the role of main character Alba, face down a series of puzzles, platforming sections and spindle-limbed black blob enemies on your way. You begin at first as a protector. In the opening sequence an adult, wolf-stag guardian creature is slain by this rising threat. You, the only human in the game and an implied fellow guardian of the natural world, are left to guard its young cub, Neva.

Even from such a simple, frequently distant side-on vantagepoint, Neva (the creature) is wonderfully realised. Cub-Neva is paradoxically timid and bold, in that way our human cubs can be. It darts ahead off-screen and yaps at you to catch up, then it reaches a high ledge you comfortably plop down from and stops, patting its feet and worrying about the jump. It drinks from forest pools and eats ripened, summer fruit from beneath the trees; it barks at enemies and then cowers and yelps at them as you do battle. I was desperately curious, when reading Nomada Studio’s citing of The Last Guardian as an influence, as to what that might mean. In the early stages it looked to be something quite special: an impetuous, richly animated creature as companion and guide, and crucially one that you must negotiate with, using one of your few actual buttons of interaction to call Neva back to you in moments of overexcitement.

As things progress, however, Nomada walks things back a bit. Less a breathing, incorrigible bundle of living systems than The Last Guardian’s Trico, Neva is instead two things: a classic companion-tool for negotiating the world; and a walking metaphor for those family members who you care for and who ultimately come to care for you.

Still, that’s effective enough. Neva is just five hours long, plus a bit extra for completionists. It’s light-touch and quick to move, sailing forward unburdened and with ample narrative momentum. After an hour or so of summer, it’s on to a multi-part autumn, the meatiest part of the game and perhaps predictably, the one charting Neva’s adolescence and your prime, as things take a darker turn. Puzzles and platforming evolve from simply making sure you spot the right walkable ledges among the game’s sumptuously detailed backgrounds (a clever use of everything from barely-there grassy patches to hard, glossy lines, depending on the environment, makes the typical yellow-ledge approach look positively ancient), to brief but intricate moments of spatial reasoning.

Many of these involve totems, small clusters of seemingly human-made structures where you’ll need to whack a gong to transform the nearby environment. Staircases shift; obelisks rise and fall; floating, circular walkways rotate. Others are simpler platforming challenges, with the best moments turning on one smart decision to let you thread your two main abilities – double-jumping and dashing – in whatever order you please. Simply allowing you to jump, dash, jump again, for instance (with that dash also acting as a ‘dodge’, getting you through otherwise lethal obstacles), opens up a world of aerial manoeuvrability. It’s also precise, mercifully, as the challenges can be exacting at times. The frequent position you’ll find yourself in is simply: huh, how do I get around that? (Sometimes the puzzle-platforming is a bit more elaborate, but the frequent solution is just: skill).

One particular moment, a good chunk of the way in, deserves a special mention here: a sequences of reflections, on mirrored lakes or beside mirrored walls implying a kind of secondary hidden realm, where you must move your actual character on the left, for instance, while keeping an eye on your reflection moving in the opposite direction to the right. This escalates wonderfully – among reflected stars and clouds, under the blue-black moonlight, across crunching snow, it’s a bit of genuine magic. But then it comes to something of an abrupt halt. Neva is a short game, clearly wary of outstaying its welcome, and similarly cautious of not overdoing a particularly neat trick out of many, but I do wish its best moments built just a bit further, and went on just a tad longer.

Neva’s world, much the same as that of its predecessor Gris, is continuously ephemeral and metaphorical like this. While you begin in a familiar kind of eldritch forest, soon you’re scaling fractured, floating trees that rise up beyond the clouds, or plummeting through layer upon layer of shrouded, abstract landmass into the void below.

It’s worth emphasising that all of this is just exquisitely, relentlessly pretty. Neva as a whole is a festival of colour, a total rebuttal of dullness, each area and season its own bold and brilliant wash. Candy pink on verdant fields, shimmering blue and deep purple, crimson against pitch black. At times this is a touch on-the-nose: as the narrative shifts, so do the colours, and indeed their tones, from richness and almost wincingly sweet, bright vividity in the height of spring or summer (both seasonally and the characters’ lives) to washed out, sallow paleness in moments of isolation, or inky-dark depths of despair.

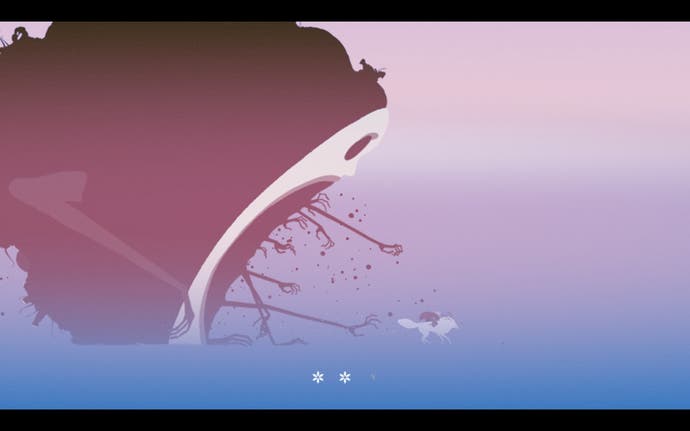

Those darkest moments are naturally where the combat becomes its most intense. Neva’s enemies are oddly familiar, for something so unsettling and strange – almost 1:1 recreations of the twig-armed, white-masked gourmand No-Face from Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away. Here they act both as disposable peons to a nameless, evil god-witch, quickly dispelled with three to five whacks of your sword, and also parts of a bubbling, rolling whole, frequently merging together to form larger enemies, animating the corpses of dead wildlife, or indeed forming twisted, unnerving environments of their own. What this means for you is: a lot of little grunts, some bosses of varying size, and some quite clever variations in between.

As Alba you have just one weapon, that sword, and little else besides a nice dodge-roll and that accompanying double-jump and air dash. The result is something straddling the line between tightly focused and just a tad repetitive. I feel obliged to decide which it is, but really it’s simply both. There are moments where whack-whack-whack with a sword can feel like a repetitive and unthinking button-mash; at other times, the rhythmic twirling into and out of the very edge of death is wonderfully tense. You have three hit-points, each one recovered by around a half dozen uninterrupted hits on an enemy, or by one of the game’s many healing fountains. Maintaining health becomes a Bloodborne-like balancing act, then, weighing risk and reward, lunging forwards to recover a third of your health just as receiving a single blow would knock you out entirely.

I have some quibbles, mind. Hitboxes on some enemies are frustratingly vague. One charging bull caused me some annoyance: having dispatched a few early encounters by dodge-rolling through their charges, a later one among a cluster of enemies didn’t seem to fancy it, my rolls through the legs failing about half the time. It turns out a double-jump and air dash was what it really took, though both of these manoeuvres finished before I reached the end of its body. The lines between invincibility mid-roll – i-frames to the fighting game nerds out there – and an enemy hit-box causing a frustrating death were never entirely clear.

My other quibble comes back to that very first point. What are Neva’s inspirations? It’s certainly inspired by Ghibli’s green fields and oily, corruptive demons. It’s inspired by the near-silence of Team Ico, its mournful architecture and emphasis on grand, protective creatures within the natural world. It’s influenced by Monument Valley‘s eerie staircase obelisks, Hollow Knight‘s glinting, darting knife in the dark; the sharp bite of mortality of, perhaps most directly, good old Bambi. But crucially, it’s influenced by Roset and Mendoza and no doubt the rest of Nomada Studio’s direct experience of the world.

The worry is what those influences add up to, beyond a recognition of greatness and some truly exceptional visual taste. They result in a game that’s overtly beautiful, but can in some moments feel like its primary goal is to simply be beautiful, in the same way its narrative beats are certainly emotional, but can also feel at times as though they’re designed simply to make you feel emotions.

This isn’t helped by a score that can climax just a little too loudly, too epically, and too often, and the somewhat overwrought system of pressing a button to hopelessly cry out “Neva”, in differing degrees of anguish, on demand. With quite a truncated runtime and not a great deal of space for narrative development beyond the initial setup, getting repeatedly blasted with operatic crescendos, maximalist visual splendour, and scenes of cute dogs in peril can occasionally mean the melodrama crosses over just slightly into mawkishness. If this were all Neva was setting out to do – be beautiful; make you feel something – then it’s undoubtedly successful. But we’re now in a time where it’s widely accepted that games can do more than that – they can explore their themes, rather than solely using them for impact – and I believe Nomada Studio knows that too.

Thankfully, Neva’s winter act is its saviour. Alone, the adult Neva you’ve come to rely on now independent and absent, you climb steep hills rather than mountains, and trudge solemnly through a washed-out world you once glided over on Neva’s back, with the old enemies resurfacing yet again. Flying opponents, who you could previously take out with a kind of ranged attack command for Neva in its prime, are suddenly a real handful. Clusters of basic enemies are more menacing, without adult Neva’s health-restoring howls between fights. It’s a simple trick, but an effective one.

It’s also only a relatively brief sequence, compared to the game’s other seasons. Part of me wonders if Nomada could’ve been a little braver here, drawing this disempowerment out a little longer, exploring the ‘winter’ chapter of life with a little more depth. But I think it’s just about enough. This is where Neva explores the “full cycle” of care mentioned by Roset and Mendoza, and where their own inspirations, eventually, come through to the fore.

Neva could do more. It could go beyond leaning on the aesthetics of the games that inspire it and attempt to engage with their themes – of Ghibli’s parables on industrialisation or coming-of-age or war; or Team Ico’s obsession with movement, sentience and natural harmony – with greater sophistication or nuance. But it still brings inspiration of its own. In other words, that original Cronenburg question maybe just slightly misses the point. Everyone has contemporary reference points, after all. Simply nodding to them isn’t enough, but as Neva shows, it only takes the lightest touch of your own experience and insight to create something that still feels wonderfully new.

A copy of Neva was provided for review by Devolver.

Add comment