In Pathologic 2 you played an exhausted surgeon who between incisions would scramble through piles of rubbish for a handful of nuts to keep himself alive. In Pathologic 3 the developers want you to approach the same plague-stricken town from a different perspective. This time you’re a well-fed and well-dressed city doctor whose pompous attitude and diagnosing minigame makes him more like Hugh Laurie’s Dr House than the scroungey hero of a survival game. Pathologic 3 Quarantine is a demo on Steam that lets you try out this secondary hero, the Bachelor, and it sets the tone for another trip into Ice-Pick Lodge’s janky-if-interesting townscape.

We got the gist when the game was announced in October last year. You’ll be playing as Dr Daniil Dankovsky, a vaguely disgraced and obsessive doctor who arrives in the Steppe town just in time for it to become wracked by the Sand Pest, an illness that quickly spreads from district to district. In this demo, you relive the fifth day of the plague via a flashback during an interrogation (this is a frame story that allows for retrying “failed” days – more on it later).

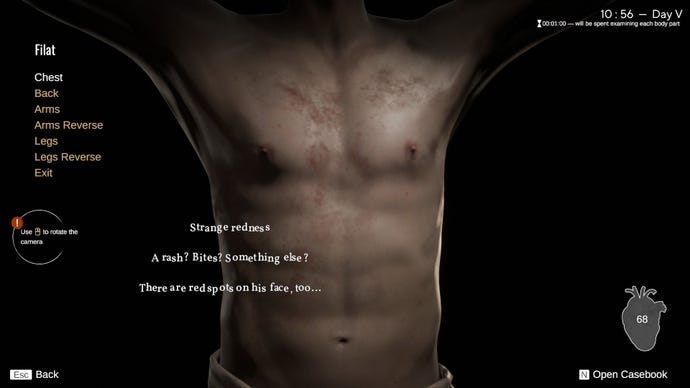

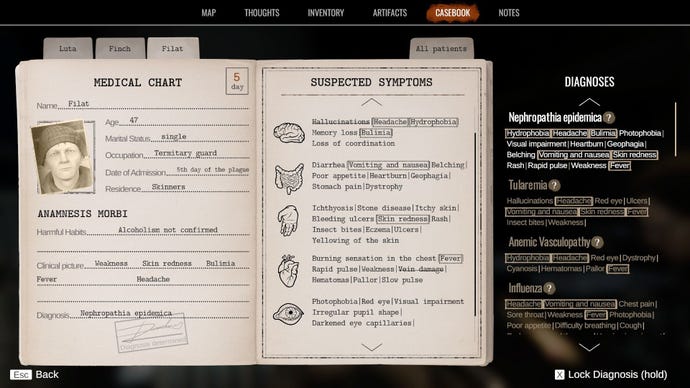

Instead of battling a handful of meters governing hunger, exhaustion, thirst, and infection, the doc will spend that day interrogating patients, noting their symptoms in a casebook, and investigating their lives to uncover any secrets they’re hiding which might inform his diagnoses. It’s not the plague that ails these patients, but a library of other diseases that you’ll need to pick and choose from when giving the final diagnosis. The Bachelor’s theory is that other illnesses can slow the progress of the plague, an idea that brings to mind the embattled immune system of Mr Burns from the Simpsons. Probably not the image the creators intended, but that is really what he thinks, medical degree be damned.

Judging from the demo, this loop of asking questions, noting symptoms, and crossing town to do a little detective work, has a lot of promise. It lends the sequel a very different feel. There is still one big meter to worry about though, described as the “seesaw” in your head. This is basically a meter that swings between mania in red and apathy in blue. Degenerating too far into blue apathy will see your movement speed slow to a painful crawl. To counteract this natural decline, you can huff tobacco and take strychnine in small doses to lurch into red mania. This regains your faster movement, but too much will harm your health and it can become addictive. The effects of each drug will lessen over time. There are other options to get back up to manic speed. Furiously kicking trash containers in the street, for example, will boost your mania (and provoke an ethereal inner voice that mocks you for being frustrated).

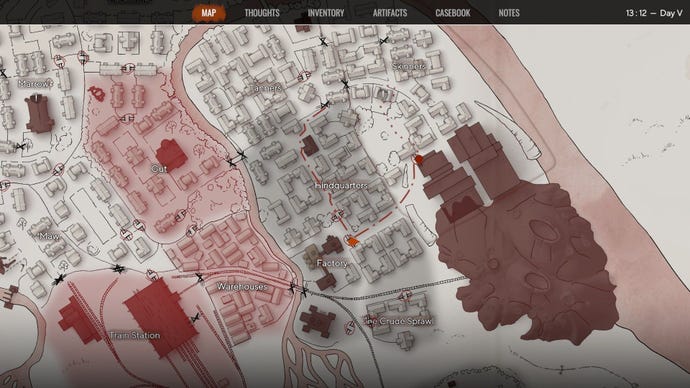

As for the streets themselves, well. Navigating the town is not the open worldish wander of Pathologic 2, but a more fast-travellish matter of plotting a course on the town’s map. A red dot flits across this map towards your destination, only bringing you back into the game world if you pass through a “dangerous” or infected district. When this happens, you’ll need to navigate on foot, rooting about for drugs in abandoned suitcases, kicking garbage cans, avoiding the outstretched arms of the infected pleading for help, and cranking up a prototype do-hickey that evaporates germs in a wide radius around you.

In more riotous districts armed or punchy men will run at you and try to murder you on the cobblestones. Here comes a familiar bit of not-quite-combat – the doctor has a revolver, and unlike the Haruspex of the previous game, he can’t hand it to a child beggar in return for a few matchsticks and a bit of old bread. It’s your permanent weapon, if not always loaded with actual bullets. Holding your gun up at approaching reprobates will make them freeze and raise their arms in hesitation. It doesn’t quite ape the face-offs of dustily forgotten adventure I Am Alive, which did a similar trick way back in 2012. But it does allow for a frantic dash through fiery neighbourhoods. This never needs to fully degenerate into a shootout, provided you keep pausing to point your gun at anyone suspicious.

If all this is sounding to you – a Pathologic uberfan – like things are getting a little too video gamey and not opaque, buggy, and anxiety-inducing enough, then relax. There were still plenty of moments in which I felt lost and sorry for myself. Sometimes during dialogue the perspective flips completely, and you are suddenly speaking as an interrogator or assistant instead of the Bachelor. There is a lot of unsettling music, and that same megaliterate dialogue that oscillates between janksome nonsense and lyrical threat. Sometimes it feels familiar simply due to bugs, like the one that had me walking around an empty field looking for a house that only existed on the map and not in the actual town. This is very Pathologic.

For all its stitched-togetherness, the Quarantine demo remains good at building atmosphere. As a taster menu for the unreliable narrator story that is planned for the full game, it is flavourful and stacked with familiar names and faces for long-suffering fans. As a showcase for what the player will be doing it’s also something of a disjointed mess. I’m writing out many of its features in simple terms, but the demo itself doesn’t always deliver them that way, with minimal tutorials and a UI that mostly lets you figure things out yourself.

Some quirks annoy me more than others. Characters often deliver long audio lines that are distinct from what’s written in their dialogue text, for example, causing a linguistic clash in my brain. In many text-heavy games if you open a dialogue with a character and they address you audibly, they’ll tend to limit it to “hey” or “yes?” or “what is it?”. Some short interjection that just signals a conversation is starting, but doesn’t distract from the important text. But Pathologic games hate being ordinary. So here, characters will muse full inner monologuey thoughts aloud, dense ponderings that sometimes border on poetry. If you’re like me and can’t read a sentence while someone talks to you, it makes for an interruptive and frictional reading experience. It’s like trying to scan the menu at a Spanish restaurant while the waiter explains Aristotelian metaphysics. Does this game want me to read or to listen? I don’t know.

As ever with Ice-Pick Lodge games, it’s hard to tell if this is intentional, meant to heighten some sense of unease, or if they are simply the result of a contrarian design philosophy (or a basic reluctance to act on feedback). Players of these games tend to give credit where it’s due, as when it provokes thoughtful pain, but they also ascribe meaning to the jank and cut corners of a series that, let’s face it, is sometimes simply borked. For me, the Quarantine demo, like all Pathologics before, remains interesting to read and write about, less so to actually play. Sometimes a delight, sometimes a chore.

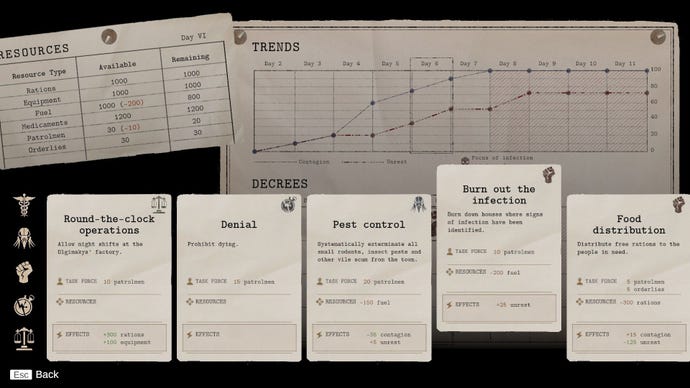

Towards the end of the fifth day, some other tasks are dangled in front of you. As the only doctor in town, the municipal government has given you emergency powers. You can make decrees using a display board in your home, for example. Decrees such as “Pest control”, which uses up patrolmen but reduces the contagion level of the town. Or a “Food Distribution” decree, which greatly lowers unrest levels but will spread the contagion further. There is also a flat out “Denial” decree which simply reads “prohibit dying” (it has no effect). But these are abstractions on a graph, and there isn’t time in the demo to see how your decrees are reflected in the world.

One big feature that isn’t fully fleshed out in the demo is the time travelling idea. The doctor’s struggle to contain the illness takes place over twelve days. At certain points you’ll be able to wind back the clock and revisit a previous day. But this requires a certain amount of Amalgam, a white substance “acquired through successful euthanasia and breaking mirrors”. (Yes, you earn time travel gunge by playing a euthanasia minigame where you ease the passing of dying people in the street by administering morphine or other drugs. I’ll let you unpack that one yourself, it’s too early in the day for me.)

You’ll use Amalgam to turn back a grandfather clock in your home tower and revisit those past days. But the further back you go the more it’ll cost. And this demo cuts off before you zip back to the past. It’s not clear how deep this rewind feature is. Do you just go back and change a few things? Or do you repeat the whole day again? Does it undo everything you’ve enacted up until that point? In other words, if it’s day seven and I travel back to day two, will I have to replay days three to seven yet again?

None of this is clear. It may prove a novel save system (the game still autosaves throughout each day too) or it might just end up softlocking you into an Amalgamless failure spiral. Whether it frustrates players or intrigues them, we’ll see. Probably both, knowing Pathologic.

And that’s the thing. This sequel feels, even from the Quarantine demo alone, like it is exclusively for long-in-the-tooth explorers of this town. And some of those may already be miffed that all this was originally meant to appear in Pathologic 2. Some good will earned by the studio over the years might have also dried up due to the recent news that the founder of Ice-Pick Lodge, Nikolay Dybowski, left the studio earlier this month amid allegations of abuse and kidnapping. The project continues without him, but how much more blood can the developers extract from a cult favourite before even the most ardent fans get tired of talking bulls and women arranged in transparently sexy compositions? The original Pathologic did include one playable woman, the Changeling, who now takes a back seat as Ice-Pick Lodge work towards a release for Pathologic 3 this year.

We’ll likely have a full review of the sequel once it’s out. The previous game frustrated me on release but I did enjoy its eerie world much more after it was patched to allow for other modes of difficulty. Let’s hope Pathologic 3 can retain some of that otherworldly appeal.

Source link

Add comment