Like all good Westerns, Rosewater starts on a train.

Need to know

What is it? Western point-and-click adventure game, and a spiritual successor to Lamplight City

Release date: March 27, 2025

Expect to pay: $20 / £17

Developer: Grundislav Games

Publisher: Application Systems Heidelberg

Reviewed on: Windows 11, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060, AMD Ryzen 9 4900HS, 16GB RAM

Steam Deck: Playable

Multiplayer? N/A

Link: Official site

Journalist Harley Leger is on her way to town to take a job at the Rosewater Post, a small but competitive newspaper looking to broaden its reach. Her first assignment is interviewing Gentleman Jake Ackerman, a Wild West showman who’s come to town, but her involvement with him quickly spirals into a treasure hunt that takes her, Jake, and their ragtag crew of misfits all across the West.

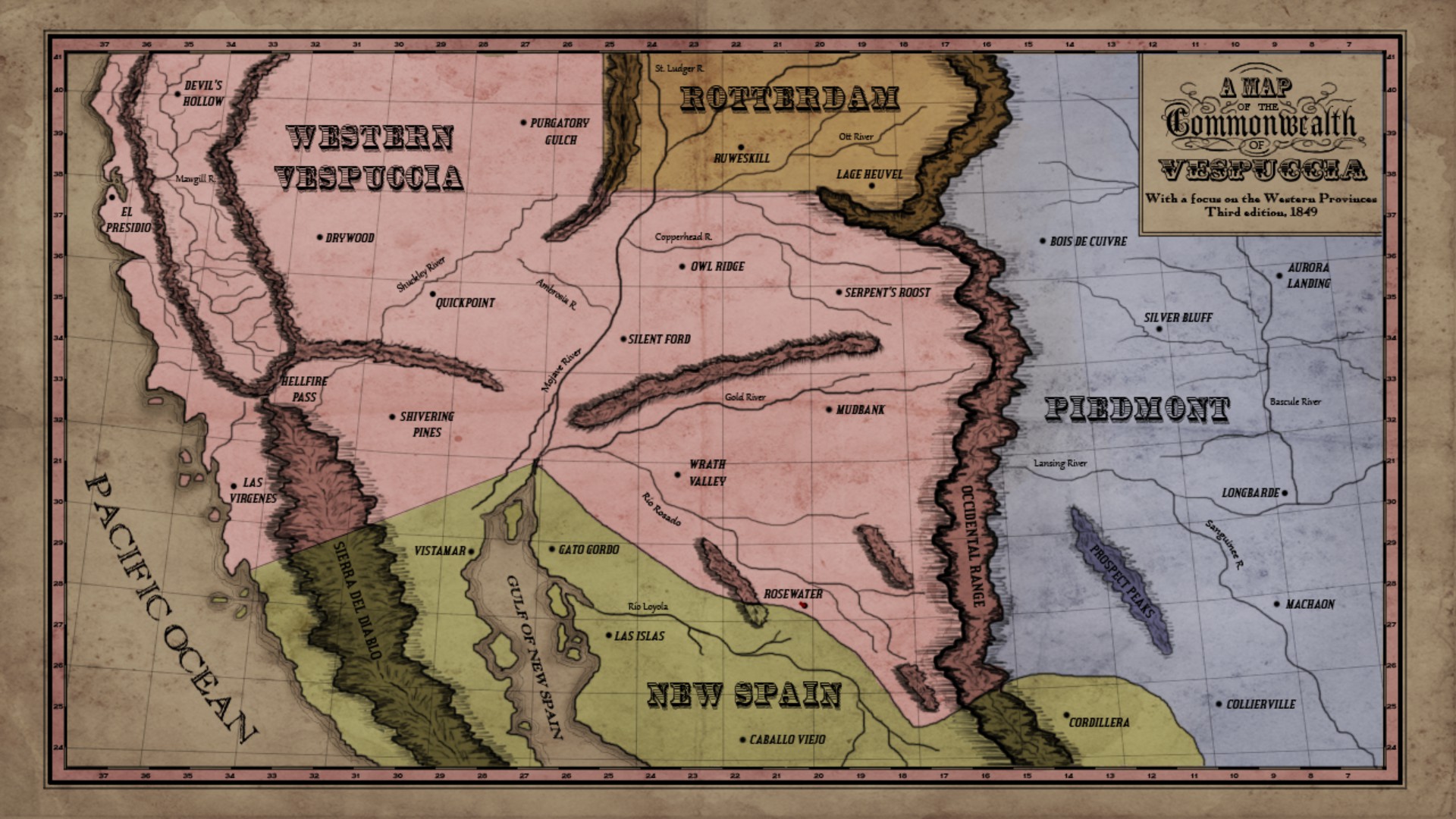

The West, in Rosewater, is a bit different than you might remember: Society is reeling from the catastrophic consequences of recent developments in the field of “aethericity,” continuing the steampunk-alternate history setting from Rosewater’s predecessor Lamplight City. This isn’t a West ruled by lone men on horses and quickdraw gunplay, where it’s the toughest and the quickest that get out alive, but one steeped in a sense of intrigue and mystery that pulls the genre away from its bloody roots.

As a journalist, Harley’s an excellent protagonist for the role. Instead of a revolver her weapons are curiosity, stubbornness, and a nose for the truth; instead of a hunt for gold she’s hunting for a story.

Rosewater has a habit of taking western staples and giving them a bit of a twist. Instead of the somber journey of a silent loner Rosewater is a chattering road trip of Harley and, it seems, everyone else she can find: boastful Jake and his talented assistant Danny Luo, charming rebel leader Filomeno Marquez (Phil for short), soft-spoken aspiring doctor Nadine Redbird, and their caravan driver, hard-as-nails Lola Johnson. The majority of the game takes place in Lola’s wagon as they make their way to El Presidio, encountering settlers, travelers, bandits, merchants, refugees, con men, and laborers.

There’s not a single time that they drive by with cold focus on their goal. Instead, they stop to talk, to help, and to poke around. Every time. Absent a ruthless pursuit for justice or gold, Rosewater is relaxed to the point of feeling aimless.

The road trip itself is an extended series of vignettes, varying widely in depth and complexity. Some smaller events are randomized, and can be encountered any time in the story or skipped entirely. Others are complicated setpiece scenes with more interesting puzzles and a focus on the companion characters, where Harley is not just doing her own searching but directing and assisting the others, learning about them at the same time as they all learn about the new people and places they’re encountering.

It’s charming to watch Danny get scammed by a fake psychic or Lola pretend she’s not enamored with a traveling family’s neglected puppy, and occasionally these scenes will lead into fairly intense companion interactions, as in a scene where Phil runs into former friends who became refugees because of choices he’d made.

As the trip progresses, puzzles get more complicated—as in all good adventure games, one drove me to the point of utter frustration only to learn that the obvious answer had been under my nose the whole time—but in general they require just enough work to stay engaging without losing my attention. I had an especially good time with the side story of a retired sea captain whose home the gang retreats to during a storm: with multiple layered smaller puzzles in a limited area centered around the background of a single character, it makes the climactic scene of the subplot—an extremely goofy yet quite charming seance-ish scenario that involves everyone dressing up like people from the captain’s past—feel like a worthwhile reward for the time spent snooping around his house.

Less entertaining are the minigames, which mostly serve to waste time until Harley can determine she is actually not very good at the thing she is trying to do and hand it off to a more talented companion. Simpler ones like fishing are forgivable (move your mouse in the opposite direction the fish is pulling) but the less said for Harley’s attempts at sharpshooting, the better (click that thing that’s moving fast oh my god so fast!). Similarly, a map mechanic introduced late in the game feels distracting, and is made almost illegible by the simplicity of the art style. Luckily these detours don’t come up too often.

Rosewater is sun-baked and unhurried. The lack of urgency works fits Harley, whose dry humor and sense of general competence carries much of the game. Though the group find themselves in occasionally bizarre or extraordinary situations—in the lab of a mad scientist, swept up with a patrolling military party, ambushed by psuedo-Pinkertons, or trapped with overly friendly religious cultists—Harley always keeps her cool. The game especially shines in her short moments of narration and her rarely-referenced diary, which contains some of Rosewater’s best writing and lends an incredible sense of atmosphere to its interpretation of the West.

Of course, the sunny lethargy can’t last. There’s a narrowing of focus as Rosewater approaches the climax, and a feeling of claustrophobia from the return to urbanity as the group nears El Presidio. My trepidation grew alongside the characters; there is a sense that the eyes of the world have returned to us. This is a stark contrast with the rest of the game, where I had the ever-present sense that the world has been left behind, that the grand events of history have already happened, and that the places and people around which Harley finds herself are not pointed towards any particular future but instead pointed away from this unseen past.

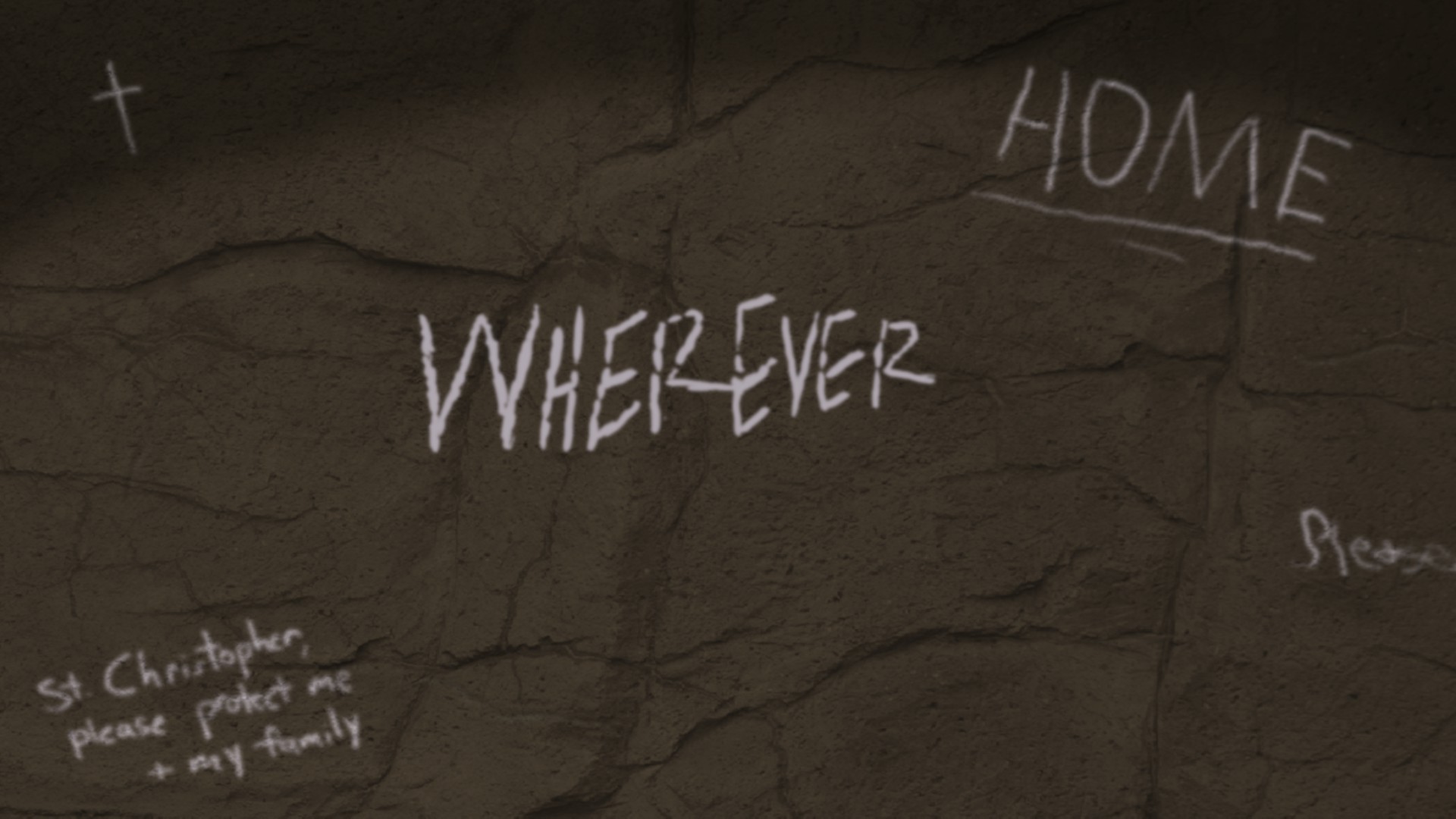

The myth of the West, in Rosewater, is less one of expansionism and settlement and more one of refuge. Rosewater does not ignore the problematic history of the Western genre—in fact, it spends a great deal of time with the consequences of the imperialist brutality against both Native tribes and the New Spanish—but it finds the bulk of its empathy in stories other than bloodshed.

Everywhere Harley and her companions go they find people who are trying to figure out how to live. If Rosewater buys into one myth of the West more than anything, it’s this: the West in Rosewater is a future, uncharted, undefined, for those who come to it and for those who are already there.

It’s why it feels right that Harley can make her journey equipped with a notebook and not a gun. The treasure they’ve set out to hunt is far removed from its origin: the fortune of a scientist hiding from a scandal following a catastrophe in a city far away, where some of these characters might have been once but no longer are now. Without a race to the gold or a hunt for a killer, there’s time for her to look for her future and for her story, and help her companions and the people she meets along the way look for the same.

It feels appropriate for a game like Rosewater and what it’s trying to be: a version of the West that we know, but not quite.

Source link

Add comment