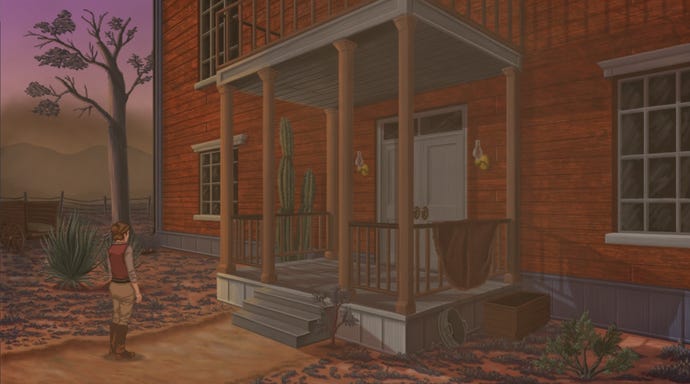

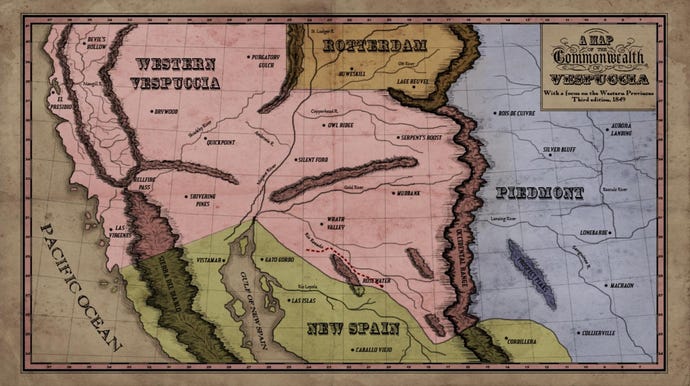

Rosewater is Francisco González’s latest adventure game set in the alternate history of Lamplight City. It swaps the murky Victorian gutters of its predecessor for cacti and lavender sunsets in a reimagined American West circa 1850. But as hard as I try to imagine myself as a ‘venturin’ cowpoke, I wind up feeling more like a prospector, sifting through dust in hopes of finding the gold that I see glimmers of out here

The story puts you on the trail of gold, after all. Shortly after arriving in the titular frontier town to take a job at the local paper (ah, memories), Harley Leger winds up embroiled in a search for the lost fortune of a scientist exiled for meddling with the sinister, quasi-magical “aether.” What would otherwise be a fairly tired I Can’t Believe It’s Not Steampunk premise is saved by a bit of distance from the setting’s urban epicenter. Out on the range, such wonders of technology feel mysterious.

But Rosewater is not a mystery game, or at least not a detective game like its predecessor. It’s a straight up and down, God’s honest point-and-click adventure. It abandons Lamplight City’s dialogue-based method of interaction for a more traditional inventory, which I have the pleasure of watching fill with drek, then winnow as I tackle problems that could easily be solved by a trip to my local hardware store.

The first two hours follow Harley as she puts together a team of fortune-seekers. There’s the smooth-talking showman, the gentle healer, all charming in an Ocean’s Eleven kind of way. Mixed into the linear puzzle sequences, the crew occasionally offers competing strategies for tackling challenges. These strategies range in viability. While I was using my nerd brain to crack the combination to a locked door, my buddy Phil was whispering in my ear about how easily a giant explosion could handle it. Peace, Phil. There will be time.

Harley is the odd one out. Her well-written dialogue gestures at a scrappy past and journalistic chops, but her main contribution to the crew is being the protagonist of a point-and-click adventure game – or as one character puts it: “Harley, you’re good at finding things!” – in which capacity she becomes anything the puzzle demands. One minute she’s a better sharpshot than the crew’s sharpshot, the next she’s running a theater troupe better than the crew’s trouper. That, and she’s a vessel for the Tombstone-level putdowns that Rosewater generously lavishes upon audiences of taste.

It’s not long before Harley & Co. depart Rosewater, and the bulk of the game becomes less of a heist and more of a protracted road trip with your unemployed friends. Some contrivance halts the caravan’s progress, and all of a sudden you’re (for example) playing dress-up as a retired sea captain’s dead crew in order to coax him out of trauma-induced catatonia.

That’s not a knock against Rosewater’s excellent sense of humor, although this particular sequence isn’t played for laughs. But scenes as unmoored from reality as these make it hard to pick up the thread of logic that’s supposed to lead me along puzzle by puzzle and scene by scene. Achievements indicate branching choices, but for the life of me I can’t think of many points where I could have influenced events one way or another, save for some moments where I saw a clear narrative path but couldn’t find the right interactable to pursue it. My ending tied up the big questions just fine, but in its aimlessness Rosewater’s plot leans more Coen brothers than Sergio Leone.

Every area of the game struggles with answering “why?” Why does Danny need this specifically shaped rock to build a memorial? Why does tracking hoofprints involve clicking through a dozen identical screens, rather than two or three? Why are we stopping to improve a struggling actor’s latest play, when literally nothing is stopping us from just continuing towards our objective?

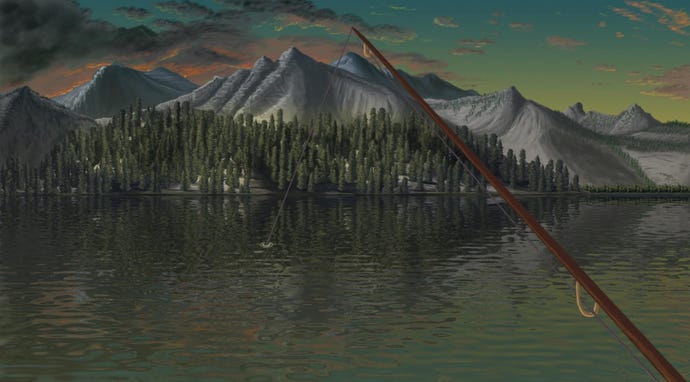

The answers, I think, are twofold. Another stop sees Harley’s crew linking up with a family of traveling merchants. The backdrops, without fail, are stunningly gorgeous. Phil strums the guitar and sings an original composition by Francisco González’s cousin. Why did we stop here? Because when its stars align, Rosewater is capable of real beauty.

It’s one of those games that, if I had played it from the dusty disk drive of my parents’ Dell Inspiron circa 2010, I would think about it once every couple of weeks. In a decade of updates to point-and-click formulas, Rosewater refuses to update basically anything, for better and for worse. Arbitrary sequences of item interactions and characters with extremely specific preferences are a part of that formula. Why did we stop here? Because it’s where the puzzles are.

My own enjoyment of Rosewater feels like a contagion in that way. Not just from the joy that palpably went into its creation, or the fact that the star-studded voice cast (including Arthur Morgan and the narrator of Baldur’s Gate 3) clearly had the time of their lives. I enjoy it because it reminds me of the games I could spend a month on back in the aughts. Other times, though – when I’ve spent a half hour wandering around, exhausting dialogue options in hopes of connecting the dots that will let me move on – I’m reminded of the adventure games I’ve played in the intervening decade which iron out the snags that Rosewater so often gets stuck on.

This review was based on a free review copy supplied by the developer.

Add comment