When I was little, I really liked what I saw of Shin chan, even if it was just largely flashes of his bare arse on Japanese TV. He seemed mischievous, a bit of a menace, and part of a fun family dynamic. Flash forward to now and I can only describe the lad as… jarring. At least, I think he’s an odd flag-bearer for a series of games where you live out a nostalgic, Japanese summer in the countryside.

And I think it’s doubly weird that Shin chan: Shiro And The Coal Town opts for a collectathon approach, that doesn’t necessarily make the act of living out a Cicada Summer all that mesmerising. But, and this is a big but: I can’t stop thinking about it. Of all the games of 2024, Coal Town may have left the biggest impression on me. In a way, I hope it does for you, too.

Coal Town, like its predecessor, is a spiritual successor to the Boku no Natsuyasumi (My Summer Vacation) games. Where Natsuyasumi starred a harmless young lad who stays with his extended family in the Japanese countryside, Coal Town mirrors this setup but Shin chan-ifies it. You stay in a traditional country abode in Akita prefecture and you’re to fish and to catch bugs and to, largely, exist in a pleasant manner.

Except that no, you’re not a pleasant young lad, you’re Shin chan: a five year old who shouldn’t know the concept of horniness, but it lives ever present within him and bursts forth whenever he interacts with a woman (his family are also perpetually horny, so it makes sense). Every time he talks, it is like thick slime oozes out of his mouth and muffles the pleasant chirps of summer. Hold the “run faster” button and he transforms into an arse-wiggling hovercraft (this is good, to be fair).

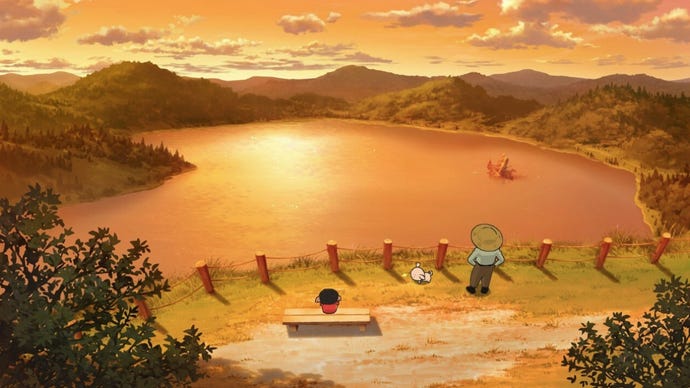

Being Shin chan is jarring and at times, a bit exhausting. But the general rhythm of the game is nice, and illustrated by frankly gorgeous art. Early on the town is split into manageable vignettes: an over-the-top shot of irrigation channels and rice paddies, a bus stop nested atop a cliff view of Akita, vegetable stands and lovely benches, and each room of the traditional house itself (the genkan, the tatami floors, the sliding doors looking out onto verdant green, all bringing back fond memories of my own grandad’s place). You run between these artworks, collecting wildlife and picking herbs for the townsfolk. And each time you move between spaces, it’ll run down the clock, until day turns to an amber afternoon, and Shin chan’s parents tell him to come back inside before it transitions into a starry night.

No, Coal Town doesn’t play like Animal Crossing, in the sense that in-game time continues alongside real life time. Put down Coal Town and things will resume where you left off, but it shares a similar philosophy to AC. Gradually, you create a daily routine that grows alongside the town’s expansion. As you collect horned stag beetles and shiso leaves and carp for people, previously blocked pathways open up. For instance, kids might budge out of the way of a mountain path, which leads you to more folks, more checklists, and rarer ingredients to collect.

With progress locked behind the act of “getting stuff” that can take multiple days to blossom or harvest or appear in many cases, you absolutely shouldn’t play Coal Town in lengthy Steam Deck sessions (runs like a dream) like I did for this review. Much like dipping your jam-crusted hands into a picnic hamper, this is a game to be chewed in leisurely bursts, otherwise the time-gating can lead to you gorging yourself too quickly and burning out.

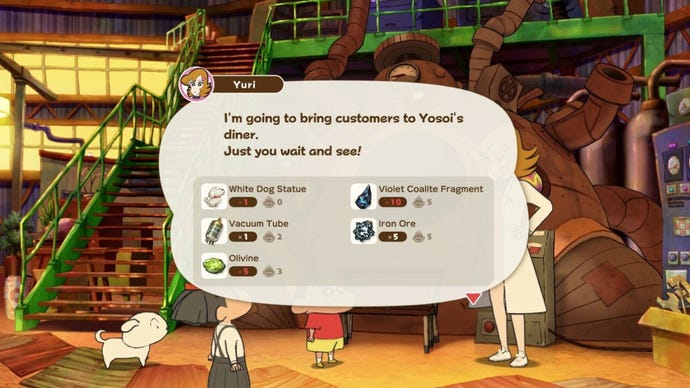

And the collectathon doesn’t stop at Akita, either. Sooner or later you’ll board a mysterious train to the once industrious Coal Town, which now lies quiet and destitute. As with Akita, you can head on over to Coal Town at any point during the day to complete tasks for its townsfolk by collecting non-wildlife things: turbines, shafts, a variety of gems and minerals. It’s here where a lot of your main quests reside, as you must provide a genius inventor with big ‘ol lists of things needed to rejuvenate the town.

Again, the checklists can grate as you portion each day to optimise your earnings as much as possible and RNG gives you the finger. But once you’ve got access to the whole of Akita and Coal Town, Shin chan does become somewhat of a clever economic tango. Thanks to trading posts (trade a butterfly for a fish, for example) at both Akita and Coal Town, you can find those elusive shopping list items through cleverly signposted links. Like say, grabbing a nan’s twenty ferns in exchange for some milk, which you’ll then trade at Coal Town’s post in exchange for a turbine. It’s undeniably satisfying when it all comes together.

The game also semi-recognises that you can’t just keep lining grandma’s pockets with cabbages, so it introduces trolley racing, which is a simple mini-game where you race against others in a minecart. The winner isn’t the person who finishes first, but the one who collects the most coins before the time limit ends. Bash into your opponent, beat them in a lap, don’t accelerate too fast around corners, and you’ll wrack up the points. It’s a good time! But it’s once again tied to the collectathon. To win those mandatory tougher races, you best collect the parts needed to fashion your cart with snazzy gear.

So yes, if you approach Shin chan like I did, the beautiful art eventually becomes a colourful blur as you motor around each vignette with a singular purpose. Harvest the tomatoes. Trade the corn. Reel the eel. Ten of those for twenty of those. I said get the f*ck outta my way nice old man, this f*cking wheeler dealer has places to BE.

Really, the act of collecting bugs and whatnot in Coal Town is a middling experience, perhaps elevated to “perfectly fine” if you’re a checkbox sicko. And yet, I find the game occupies a spot in my head I can’t seem to shake. And I think it’s down to what the game stands for, which is this: the Japanese countryside deserves your attention.

When I told my mum (she’s Japanese) about Coal Town trying to capture folks’ nostalgia for Japanese summers spent in the countryside, she made a good point. “Lots of Japanese kids nowadays won’t have had this experience when they grow up”, which I hadn’t thought about before. In a way my mum’s point is quite sad and, almost certainly, a reflection of Japan’s current relationship with the countryside. Chill in Coal Town’s onsen and you’ll overhear a miner mention it’s a shame his son has moved away to the city. Townsfolk around Akita are surprised to see you, a visitor of all things.

Of course, Coal Town is a representation of rural Japan’s forgotten industry. A rusted, dwindling community of people succumbing to the winds of change. For Shin chan, it’s a reality, a place he and his pup Shiro explore on the daily. To the adult members of his family? It’s nothing but Shin chan playing pretend; a dream. And as your presence as a member of the new generation uplifts both Akita and Coal Town with more visitors and vibrancy and a rediscovery of their histories, it makes you wonder – is it all, in fact, a futile dream?

No, Shin chan: Shiro And The Coal Town doesn’t pretend to find a solution to Japan’s societal issues. But what it will do is, hopefully, make more kids interested in the countryside. Perhaps induce in those who have nostalgia for Japanese summers a desire for rediscovery, a need to get back out there and experience it again – or even to share that nostalgia with their loved ones. Maybe, it’ll just help everyone else discover even a slice of sunny joy through a screen.

So no matter if the game’s a bit of a grind, it’s a rather gorgeous one, all things considered. And I know for certain that if I visit Akita, it’ll be impossible not to think of Shin chan… and his bare arse.

Add comment