Warm-hearted, funny, and never less than sincere, Wanderstop is a pleasant place to while away the time, though less successful as a vehicle for mindfulness in itself.

If you weren’t already worried about game developers – and, heck, you really should be by now – the growing emergence of games explicitly about burnout is certainly a good reason to start. Wanderstop, in a similar vein to last summer’s Dungeons of Hinterberg, is exactly that, only this time instead of opting for a breezy vacation to get away from it all, your location is a little more confined. Imagine Alice in Wonderland except, instead of a whole forest to act as her psychological gauntlet, Alice is trapped in a single clearing that’s been turned into a kind of max-security plant-based rehab facility.

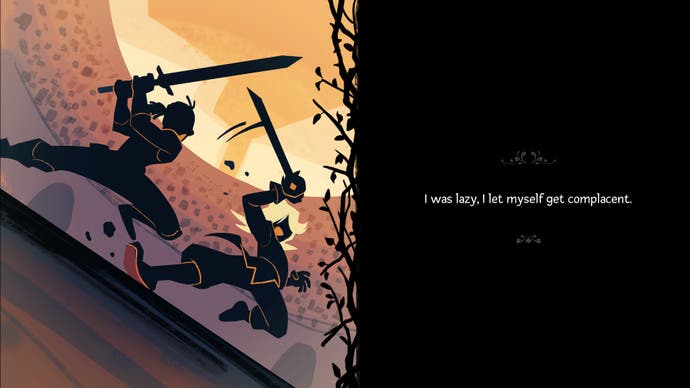

Sinister as it sounds when you put it on paper, Wanderstop, from the new studio Ivy Road formed by The Stanley Parable‘s Davey Wreden and Gone Home‘s Karla Zimonja, is sincerely lovely. Protagonist Alta, a lifelong ‘fighter’ by trade, has seen her years-long undefeated streak, brought about through a relentless pursuit of perfection, come to a sudden and unexplainable end. On a search for answers from her old master here in the mysterious woods, suddenly she finds herself unable to lift her sword, a kind of inverse King Arthur, as though her own subconscious no longer deems her worthy. She’s rescued from the forest floor by Boro, the happy-go-lucky owner of Wanderstop, a strange tea shop that presents itself to travellers in need. And here Alta must stay, making tea for increasingly weird passers-by and bouncing her restless leg, until she regains the strength, perspective, or whatever it may be that she needs to carry her sword again and leave.

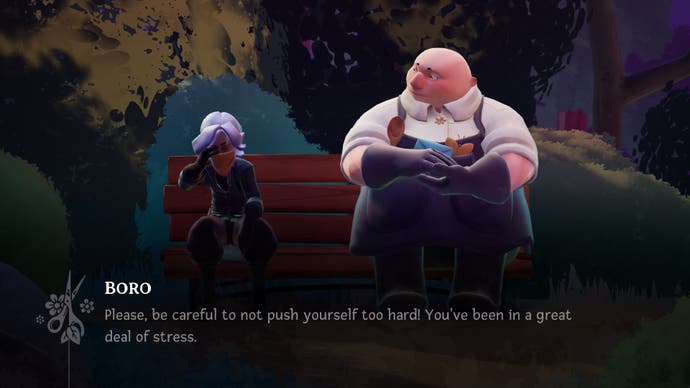

As much as there are darker corners to Alta’s psyche, Wanderstop’s story is told with the warmest of hearts. The intention here is to provide a kind of welcoming hug, a guided mediation for the player as much as Alta herself through concepts of purpose, work ethic, self-acceptance, ambition and exhaustion. Its actual successes are mixed, but much the same as lovely Boro, at no point does it ever dip below pleasant, gentle-spirited and admirably kind.

Boro, at once simple and wise, is really the heart of Wanderstop, your go-to for functional questions about how gardening works as well as more philosophical musings on boredom (sometimes it’s good to be bored!) or what to do next (sometimes it’s good for there to be nothing to do!) or how to solve Alta’s deepest problems (typically: sometimes it’s good to have a rest!). His first main suggestion to you, however, will be to try making some tea, which remains a common solution throughout.

This is where Wanderstop essentially splits into two games, or at least one spread across two layers. The first is a narrative one, with various dialogue options and varied outcomes, played out over its 10-15-ish hours. The second is a fairly typical farming-and-teamaking game in the burgeoning “cosy” genre (I will never not put this one in scare quotes, I’m afraid – first it was “wholesome”, until it was decided the implications of that word were too specifically moralist. “Cosy” is the workshopped alternative, which I think is almost worse – really, “twee” would be a far more accurate catch-all term for what most of these games are actually aiming for. Wanderstop, at least, has some heft to back up its ostensibly warm-n-fuzzy vibes.)

Farming works like this: you begin with seeds of a couple different colours. Planting a seed on its own turns it into a basic plant. Planting it in a row of three – either in a single block of colour or with a second placed in the middle of the row – turns it into a “small hybrid” plant, which when watered spouts seeds of its own, corresponding with the colours you planted to make it. Planting three of the same colour in a triangle shape, meanwhile, with another seed in the middle, creates a “large hybrid” that’s closer to a small tree. When watered, these grow fruit, which can then be picked and used as flavour infusions for your tea.

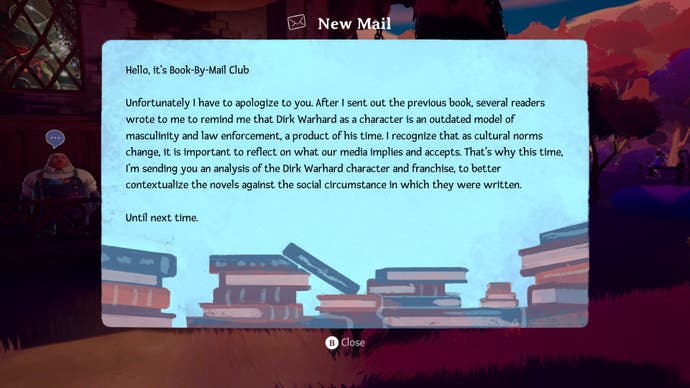

As you progress, you’ll unlock a few more colours of seeds and therefore a few more variations of small and large hybrids. There are a handful of mushrooms to be picked, which have modifying effects when placed in certain arrangements around your plants. There are weeds to be trimmed, infinitely sprouting around the tea shop’s gardens, and likewise small piles of dust to be swept. There are cute touches and the occasional little twist – a random circle of strange, unexplained mushrooms, a postbox where you can send lost parcels that seem to find their way to the clearing, and receive increasingly comical, running-joke letters and gifts of thanks in return, as well as cute little birds called Pluffins playing the obligatory yes-you-can-pet-them role.

But that cycle of ‘plant, water, harvest, look up the formation for planting something bigger, repeat’ is really the long and short of it, which feels a little bit of a shame. It’s a similar scenario with the tea-making process, which happens inside.

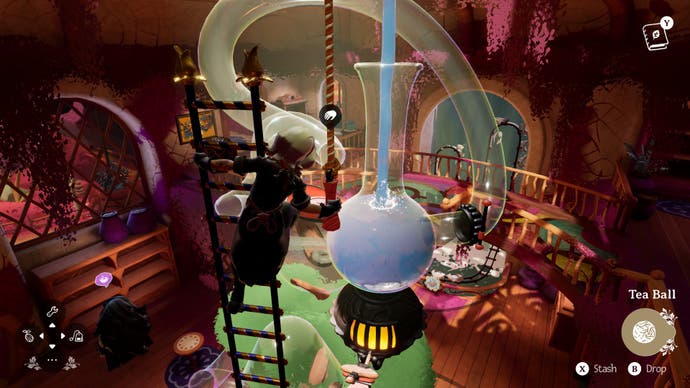

Here, in the Wonka’s factory of a tea shop, you’ll find an oversized, two-storey brewing device, operated by a sliding ladder and series of levers. For each brew you’ll need to climb a ladder to add water, then pump the billows to just the right temperature, flip a valve to send the hot water to the infuser, throw in the right ingredients, flip another valve to send it down towards the mug, place the mug (easily forgotten, as are each of these steps at first), and then pour it out, watching your sickly, swirling concoction work its way down a final, whimsical spiral spout.

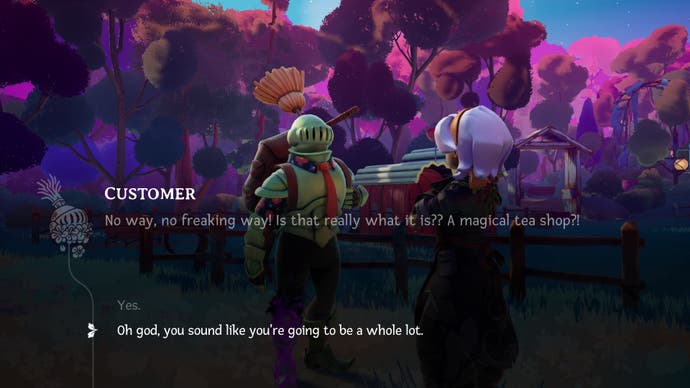

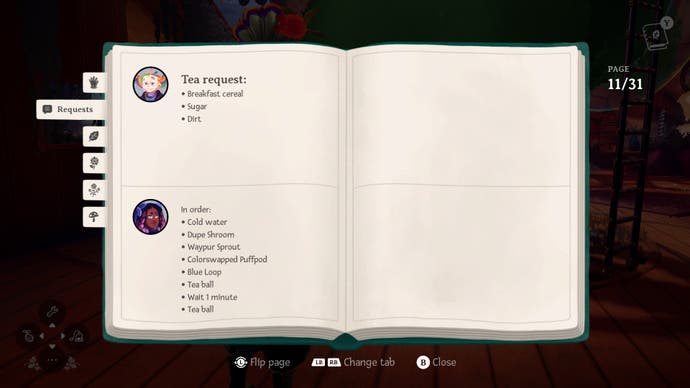

What you brew is, theoretically, up to you. Wanderstop is as much a sandbox as it is a linear narrative. If you want to advance the story, then make what the visiting customers ask of you (rarely with much of a “please,” I found, which coupled with their increasingly absurd fussiness does start to tick over from funny quirk to just plain annoying after a time). This requires a lot of checking your pocket almanac for a reminder of which fruit gives off which flavour – or which psychedelic side effect – that’s in demand, and then which tree you’ll need to quickly whip up outside to harvest it. As time goes by, the process might get slightly more convoluted – you’ll need to add ingredients in this order, or with this curious modification, or just decipher what customers mean with requests like “book tea” or, in one initially funny but then slightly overlong sequence, variations of “regular coffee”, a plant which this clearing does not typically grow.

Where the two parts of Wanderstop link is in how you advance the story. Fulfill all the requests of all the kookie customers in the current wave – typically only a couple, with maybe two requests each – and the clearing will give you a sign it’s time to move on. A refresh happens, without spoiling too much, and in that moment Alta has a chance to reflect a little deeper. So far, so cosy. But the real question is: does Wanderstop actually want you to advance the story at all?

This is where things get a little muddled. Much of Wanderstop’s writing feels dedicated to positioning it as something of an anti-game. References are made to “measurable objectives” and “specific tasks” and a sense of progress – all topics brought up, generally, as things to be avoided here at the tea shop. This is a place of tranquility and stillness, where there’s no hurry, no deeper objective, no ultimate goal to strive towards. Boro is always on hand to advise you to maybe do a few simple, recurring chores – trimming those weeds and sweeping those dust piles – or perhaps decorating by moving a few plant pots around or taking some photos for the empty frames inside the store. And you can, of course, always take the time to make a tea for yourself (or Boro!) and simply sit and reflect on its qualities and the therapy-like knack many flavours seem to have for bringing up repressed moments from Alta’s childhood.

But here’s the thing: Wanderstop is actually very video gamey, and often in the exact ways it seems to be preaching against. No measurable objectives? Well, here’s a task to feed the Pluffins five different types of tea for a reward. No overt goals to work towards? Here’s an exclamation mark above an NPC’s head. No sense of progress? Don’t worry, the NPC requests will stop after a couple of rounds, there’ll be nothing left to do, and an explicit prompt to move the world and story forwards instead.

What Wanderstop feels like it wants to be, from its many lines of dialogue, is a kind of timeless sandbox, where you can spend forever growing plants, tending to the garden, decorating and brewing tea, but its emphasis on a progressing story – with a particularly nagging urge to fix the heavy sword problem, repeatedly voiced by its protagonist throughout – stands in direct opposition to it.

Where I think this specifically falls down is in the acts of gardening and tea-making themselves, where despite the initial charm of whacky flowers and absurd contraptions, really the processes are a little repetitive and uncomplex. Or more precisely: they lack the intimate satisfaction of the right sounds, animations, tactility and feedback to really make the process something intrinsically desirable. Making tea through a lengthy series of ladder swivels and lever pulls could feel wonderful, if sufficient emphasis was put on simply making it feel wonderful. Doing so would shift this game’s emphasis from progression, task completion, achievement – the very things it advocates against – towards presentness in the moment.

This also takes me to a slightly bigger problem here, which is: you would almost certainly get better results for your own mental state by going outside and doing a bit of gardening of your own, or making yourself an actual, real, elaborate multi-stage cup of tea and then drinking it, than you would from playing Wanderstop. As anyone who’s wrestled with burnout or looked to add a bit of mindfulness to their life will hopefully tell you, there’s genuine meditative joy to be had in menial tasks. But the task itself must be something you can focus on deeply, that has intricacies and foibles, that grounds you in some way to the physical world. In a way that’s the secret to mindful video games, too: any game can be mindful; it needn’t have all the sweet and cosy trappings to get there. It just has to feel hypnotically brilliant in itself.

None of this is to say Wanderstop isn’t still utterly charming throughout. Boro, for instance, is a delight to talk to, forever upbeat, gentle, and reassuring. His actual advice, on the need to rest as you attempt to scale whatever personal mountain before you, is always very much on point. There are lovely written touches, channeling Wreden’s signature absurdity, mixing silliness with a kind of lightly-buried truth – the kind that sits somewhere between Dr. Seuss and Terry Pratchett – with particular highlights to be found in those lost parcel letters, or oddball characters whose own foibles tie themselves in all kinds of knots. Wanderstop is quite happy to not make a lick of sense, at least in its dialogue – though I do wish a bit more of Wreden’s player-trolling mischievousness made its way here from The Stanley Parable in particular. There are few structural or mechanical jokes, I found, when there might’ve been opportunity for more.

And again, Wanderstop’s world itself is utterly charming, aggressively leaning into the candy floss aesthetic of “cosy” games and the slightly sinister, sickly-sweet undertones that style can invoke. Some of its characters, even in mere minutes-long appearances, can be quite touching in their earnestness, and their passing visits and departures, and the sense of transience from them – and from the regular resetting of all your gardening work as things progress – is Wanderstop’s finest touch. Some things simply come and go – one of its most effective lessons in acceptance, stillness over progression, and simply letting be.

Wanderstop is, despite the lack of truly, intrinsically enjoyable tasks, and despite the lack of deeper cohesion between what it practices and what’s preached, still a delightful place to stop and while away the time. In many ways that feels quite apt, a tea shop that’s quite happy to exist solely for the pleasure of existing, rather than excelling. I’ve been to many places like that here in the real world. And like with those, I’m always glad I visited, if not always in a desperate rush to return. In many senses, that’s enough.

A copy of Wanderstop was provided for review by Annapurna Interactive.

Source link

Add comment